Would you like to work on 1989 after 1989 and Socialism Goes Global? Vacancies for Postdoctoral Research Associates available – apply now!

Posted on 21 December, 2017 in1989 after 1989 Job opportunities Post Socialism Rethinking 1989 Socialism

Supporting the work of Professor James Mark, 1989 after 1989 and the AHRC Socialism Goes Global, we have 3 vacancies for Postdoctoral Research Associates with immediate start.

The 12 month fixed term post with 1989 after 1989 and based in Exeter, UK will focus on the fall of state socialism in Eastern Europe in global perspective, focusing on political, economic and cultural themes.

Socialism Goes Global, supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, have two Postdoctoral Research Associate vacancies (fixed term for 9 months, based in Exeter), the first addressing themes of gender and labour and the second focusing on the themes of war, peace and authoritarianism.

Deadline for applications is 17 January 2018

Interviews anticipated late January 2018

About Exeter University

We are a Russell Group university boasting a vibrant academic community with over 21,000 students. Ranked in the top 1% of universities in the world, 98% of our research is rated as being of international quality and focuses on some of the most fundamental issues facing the world today. We encourage proactive engagement with industry, business and community partners to enhance the impact of research and education and improve the employability of our students.

The Posts

The College of Humanities wishes to recruit for three posts

- Postdoctoral Research Associate to support the work of the project 1989 after 1989: Rethinking the Fall of State Socialism in Global Perspective

http://1989after1989.exeter.ac.uk/This full-time Leverhulme Trust-funded post is available immediately on a fixed term basis for 12 months. The research will address the fall of state socialism in Eastern Europe in global perspective, focussing on political, economic and cultural themes. - Postdoctoral Research Associate to support the work of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (UK)-funded project Socialism Goes Global. Cold War Connections Between the ‘Second’ and ‘Third Worlds’

http://socialismgoesglobal.exeter.ac.uk/This full-time post is available immediately on a fixed term basis for 9 months, research will focus on the themes of gender and labour. - Postdoctoral Research Associate to support the work of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (UK)-funded project Socialism Goes Global. Cold War Connections Between the ‘Second’ and ‘Third Worlds’ http://socialismgoesglobal.exeter.ac.uk/This full-time post is available immediately on a fixed term basis for 9 months, research will focus on the themes of war, peace and authoritarianism.

Please indicate in your application which post(s) you are applying for (candidates are welcome to apply for all three).

About You

The successful applicants will have the skills to carry out research at historical archives; be able to carry out historical analysis on archival material (with guidance); possess a reading capacity in one or more languages of the region, to a high academic standard; be able to report effectively on research progress and outcomes; be able to write academic texts; and to communicate complex information, orally, in writing and electronically in academic English.

Applicants will possess a relevant PhD (or be nearing completion) or possess an equivalent qualification/experience in a related field of study. They will be able to demonstrate sufficient knowledge of research methods and techniques needed to work within these research projects. Experience of work in related research fields would be beneficial.

Interviews are expected to take place in late January 2018.

What We Can Offer You

Salary will be from £28,936 per annum pro rata within the Grade E band (£26,495 – £33,518) depending on qualifications and experience.

- Freedom (and the support) to pursue your intellectual interests and to work creatively across disciplines to produce internationally exciting research;

- Support teams that understand the University wide research and teaching goals and partner with our academics accordingly

- An Innovation, Impact and Business directorate that works closely with our academics providing specialist support for external engagement and development

- Our Exeter Academic initiative supporting high performing academics to achieve their potential and develop their career

- A beautiful campus set in the heart of stunning Devon

Please ensure you read our Job Description and Person Specification for full details of this role.

To view the Job Description and Person Specification document please click here.

To apply and view the full job advert, please follow the link to the Exeter University Vacancies Board and Application Portal.

For further information please contact:

Professor James Mark, Principal Investigator 1989 after 1989 and Socialism Goes Global – J.A.Mark@exeter.ac.uk

Natalie Taylor, Leverhulme Trust 1989 after 1989 Project Co-ordinator (works Monday-Wednesday) N.H.Taylor@exeter.ac.uk

Catherine Devenish, AHRC Socialism Goes Global Project Co-ordinator (works Thursday and Friday) C.Devenish@exeter.ac.uk

Secret Agents and the Memory of Everyday Collaboration in Communist Eastern Europe

Posted on 17 October, 2017 in1989 Area Studies Communism Eastern Europe End of Yugoslavia GDR Hungary Memory Post Socialism Rethinking 1989 Romania

Professor James Mark’s co-edited volume Secret Agents and the Memory of Everyday Collaboration in Communist Eastern Europe is now available through Anthem Press.

Professor James Mark’s co-edited volume Secret Agents and the Memory of Everyday Collaboration in Communist Eastern Europe is now available through Anthem Press.

This collection of essays addresses institutions that develop the concept of collaboration, and examines the function, social representation and history of secret police archives and institutes of national memory that create these histories of collaboration. The essays provide a comparative account of collaboration/participation across differing categories of collaborators and different social milieux throughout East-Central Europe. They also demonstrate how secret police files can be used to produce more subtle social and cultural histories of the socialist dictatorships. By interrogating the ways in which post-socialist cultures produce the idea of, and knowledge about, “collaborators,” the contributing authors provide a nuanced historical conception of “collaboration,” expanding the concept toward broader frameworks of cooperation and political participation to facilitate a better understanding of Eastern European communist regimes.

Edited by Péter Apor, Sándor Horváth and James Mark, the essays are framed into three parts – Institutes, Secret Lives and Collaborating Communities and include topics such as the Stasi Records of the former GDR; memory in Latvia, Slovak and the Czech Republics; Tito and intellectuals 1945-80; entangled stories with the Former Securitate; Regional-level Party Activists in Slovakia and priest collaboration in Slovak Catholic memory after 1989.

Edited by Péter Apor, Sándor Horváth and James Mark, the essays are framed into three parts – Institutes, Secret Lives and Collaborating Communities and include topics such as the Stasi Records of the former GDR; memory in Latvia, Slovak and the Czech Republics; Tito and intellectuals 1945-80; entangled stories with the Former Securitate; Regional-level Party Activists in Slovakia and priest collaboration in Slovak Catholic memory after 1989.

“This excellent volume marks a genuine breakthrough in our knowledge about the everyday lives of the people who made up the secret police, of their motivations and their experiences. It challenges binary visions of the past and powerfully highlights the complexity of the term ‘collaboration.’ Ultimately, it makes a case for the human factor in the history of the repressive state.”

Ulf Brunnbauer, Director, Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies, Regensburg, Germany

Table of Contents

Frameworks: Collaboration, Cooperation, Political Participation in the Communist Regimes

(The Editors)

Part 1: Institutes

Chapter 1: A Dissident Legacy, The ‘Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records of the Former GDR’ (BStU) in United Germany

(Bernd Schaefer)

Chapter 2: In Black and White? The Discourse on Polish Post-War Society by the Institute of Polish Remembrance

(Barbara Klich-Kluczewska)

Chapter 3: The Exempt Nation: Memory of Collaborationism in Contemporary Latvia

(Leva Zake)

Chapter 4: Institutes of Memory in the Slovak and Czech Republics – What Kind of Memory?

(Martin Kovanič)

Chapter 5: Closing the Past – Opening the Future. Hungarian Victims and Perpetrators of the Communist Regime

(Péter Apor and Sándor Horváth)

Chapter 6: To Collaborate and to Punish. Democracy and Transitional Justice in Romania

(Florin Abraham)

Part 2: Secret Lives

Chapter 7: ‘Resistance through Culture’ or ‘Connivance through Culture.’ Difficulties of Interpretation; Nuances, Errors, and Manipulations

(Gabriel Andreescu)

Chapter 8: Intellectuals between Collaboration and Independence. Politics and Everyday Life in the Prague Faculty of Arts in Late Socialism

(Matěj Spurný)

Chapter 9: Tito and Intellectuals – Collaboration and Support, 1945–1980

(Josip Mihaljević)

Chapter 10: Spy in the Underground. Polish Samizdat Stories

(Paweł Sowiński)

Chapter 11: Entangled Stories. On the Meaning of Collaboration with the Former Securitate

(Cristina Petrescu)

Part 3: Collaborating Communities

Chapter 12: Finding the Ways (around). Regional-level Party Activists in Slovakia

(Marína Zavacká)

Chapter 13: ‘But Who is the Party?’ History and Historiography in the Hungarian Communist Party

(Tamás Kende)

Chapter 14: Forgetting ‘Judas’. Priest Collaboration in Slovak Catholic Memory after 1989

(Agáta Drelová)

Chapter 15: Informing as Life-Style. Unofficial Collaborators of the Hungarian and the East-German State Security (Stasi) Working in the Tourism Sector

(Krisztina Slachta)

→ Order your copy through the Anthem Press website: Secret Agents and the Memory of Everyday Collaboration in Communist Eastern Europe

[Top]The Other Globalisers conference programme now available

Posted on 22 June, 2017 in1989 after 1989 Area Studies Cold War Globalisation Neoliberalism Post Socialism Rethinking 1989 Socialism

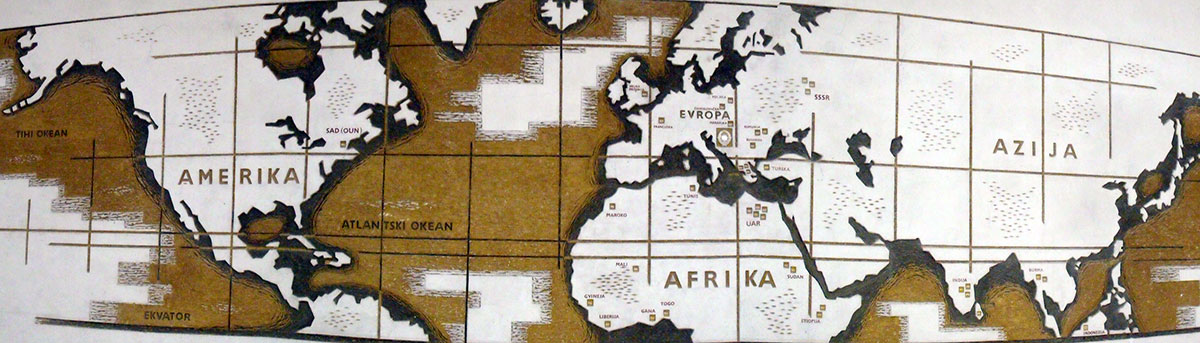

Join the 1989 after 1989 research team for our conference on the “Other Globalisers” – how the socialist and the non-aligned world shaped the rise of post-war economic globalisation. Based at Exeter, this conference is the second in a series of events exploring how processes and practices that emerged from the socialist world shaped the re-globalised world of our times.

The globalisation of the world economy has most often been portrayed as the final triumph of a neoliberal international order led by the West. By focusing on the socialist and the non-aligned world, this conference, by contrast, aims to rethink the histories of postwar globalisation by addressing forces and models of global economic interdependence other than those of Western capitalism. Acknowledging that actors from these worlds could be contributors to the emerging neoliberal consensus, as well as to other forms of regional economic integration and global trade that survive to this day, we hope to encourage an interdisciplinary dialogue between scholars using different approaches to global interconnectedness, and/or working on a variety of regions.

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME

Day 1 – July 6

The Upper Lounge, Reed Hall, University of Exeter

8.45-9.15 Welcome Drinks

9.15-9.30 Introduction by the Organisers

9.30-11.30 Panel 1: Chronologies of Socialist Globalisations

Discussant: Wolfgang Knöbl (Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung)

Marc-William Palen (University of Exeter) – Marx and Manchester: The Socialist Foundations of Post-1945 Globalisation

James Mark (University of Exeter) – Alternative? Socialist? Writing Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union into Postwar Globalisation

Christina Schwenkel (University of California – Riverside) – The Afterlife of Global Socialism: Technology and Mobility in the Postcolony

11.30-11.45 Refreshment Break

11.45-13.00 Panel 2: Global Integration

Discussant: Federico Romero (European University Institute)

Angela Romano (University of Glasgow) – Competing Plans of Pan-European Cooperation: European Community’s Policy and Soviet Proposals During the 1970s Globalization

Besnik Pula (Virginia Tech) – From Reform Socialism to Transnational Capitalism: The Political Economy of Foreign Direct Investment in Central and Eastern Europe

13.00-14.30 Lunch Break

14.30-16.30 Panel 3: Global Institutions Without Imperialism

Discussant: Richard Toye (University of Exeter)

Johanna Bockman (George Mason University) – Financial Globalisation Through Socialist and Non-Aligned Banks

Max Trecker (Institute for Contemporary History, Berlin) – Globalisation by Import Substitution? The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) and the Global South

Vlad Pașca (New Europe College) – Global Advocacy or Self-Interested Relativism? Socialist Romania, International Organizations, and the Quest for Economic Development (1960s-1980s)

Ljubica Spaskovska (University of Exeter) – The Non-Aligned, the UN and the Defeat of the ‘New International Economic Order’

16.30-16.45 Coffee Break

16.45-17.45 Round Table Discussion

Johanna Bockman (George Mason University)

Wolfgang Knöbl (Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung)

Federico Romero (European University Institute)

19.00 Drinks Reception

20.30 Conference Dinner

Day 2 – July 7

Innovation Centre, University of Exeter

8.45-9.30 Welcome Drinks

9.30-10.45 Panel 4: Neoliberalism and the Socialist and Nonaligned Worlds

Discussant: James Mark (Exeter)

Patrick Neveling (School of Oriental and African Studies) – The New International Division of Labour before the New International Economic Order: Special Economic Zones and Neoliberal Globalisation since 1947

Tobias Rupprecht (University of Exeter) – “Neoliberal” Ideas in the Communist Periphery

10.45-11.00 Refreshment Break

11.00-13.00 Panel 5: Africa and Alternative Globalisations

Discussant: Patrick Neveling (School of Oriental and African Studies)

Alanna O’Malley (Leiden University) – The Road to UNCTAD: The Exploration of Economic Sovereignty by African Countries at the United Nations, 1958-1962

Darius A’Zami (Renmin University of China) – Extra-Liberal Interdependence: The Land Commission, Heterodox Globalisation and its Roots in Sino-Tanzanian Relations in the Cold War

Theodora Dragostinova (The Ohio State University) – The Second World in the Third: Bulgarian Notions of Economic and Cultural Development in Nigeria, 1976-1982

Pavel Szobi (European University Institute) – Was Angola the “Czechoslovak Africa?” The Obstacles of the ČSSR Support for the MPLA Government Between 1975 and 1992

13.00-14.00 Lunch Break

14.00-16.00 Panel 6: Resources and Experts

Discussant: Piers Ludlow (LSE)

Ned Richardson-Little (University of Exeter) – East Germany and the Failed Dream of Global Socialist Oil Solidarity

Jan Zofka (University of Leipzig) – Coal as the Other Oil: East German Technical Experts and Industrial Expansion in the Socialist World of the 1950s

Shuxi Yin (Hefei University of Technology) – Sino-Soviet Rubber Cooperation, 1950-1953

Andrew Kloiber (McMaster University) – Brewing Global Socialism: Coffee, East Germans and the World, 1949-1989

16.15-17.00 Concluding Discussion

If you would like to attend the Other Globaliser’s conference on the 6-7 July, please contact the Project Co-ordinator, Natalie Taylor – N.H.Taylor@exeter.ac.uk

[Top]

Join us for our conference on the “Other Globalisers”, Exeter 6-7 July 2017

Posted on 23 February, 2017 in1989 after 1989 East Asia Eastern Europe Economy Globalisation Latin America Neoliberalism Post Socialism Rethinking 1989 Socialism South Africa Soviet Union

The Other Globalisers: How the Socialist and the Non-Aligned World Shaped the Rise of Post-War Economic Globalisation

Location: Exeter University, UK

Date: 6-7 July 2017

Abstract Deadline: 18 March 2017

Papers are now invited for our exciting conference addressing how the socialist and non-aligned world shaped the rise of post-war economic globalisation. This conference is the second in a series of events exploring how processes and practices that emerged from the socialist world shaped the re-globalised world of our times.

CONFERENCE SYNOPSIS

In the wake of the Second World War, the world economy began to ‘reglobalise’ – following the disintegrative processes of the interwar period. This story has most often been told as the final triumph of a neoliberal international order led by the West. Recent research, however, suggests that the creation of our modern interconnected world was not driven solely by the forces of Western capitalism, nor was it the only model of global economic interdependence that arose in the second half of the twentieth century. This conference aims to rethink the histories of postwar globalisation by focusing on the socialist and non-aligned world, whose roles in the rise of an economically interconnected world have received substantially less attention.

This conference aspires to address a wide variety of processes, practices and projects – such as efforts to create alternative systems of international trade, new business practices, through to theoretical conceptualisations of economic interconnectedness – and examine a broad range of actors, such as e.g. governments, experts, international institutions, and business ventures. It will also explore whether such initiatives were alternative at all: as recent research has suggested, actors from these worlds could be contributors to the emerging neoliberal consensus, as well as to other forms of regional economy and global trade that survive to this day. We also hope to encourage an interdisciplinary dialogue between scholars using different approaches to global interconnectedness, and/or working on a variety of regions (e.g. Latin America, Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union).

Abstracts of 300-500 words, together with an accompanying short CV should be submitted to Natalie Taylor (N.H.Taylor@exeter.ac.uk) by 18 March 2017.

The selected participants will be notified by the end of March 2017.

Funding opportunities for travel and accommodation are available, but we ask that potential contributors also explore funding opportunities at their home institutions.

This event is kindly supported by Exeter University’s Leverhulme Trust-funded project 1989 after 1989: Rethinking the Fall of State Socialism in Global Perspective.

The full call for papers is available on our conference page

→ Download the Call for Papers The Other Globalisers

[Top]

Join us for our (Re)Thinking Yugoslav Internationalism Conference in Graz, 29 September – 1 October

Posted on 20 September, 2016 in1989 after 1989 End of Yugoslavia Globalisation Rethinking 1989 Socialism

Coinciding with the 55th anniversary of the Belgrade summit and the foundation of the Non-Aligned Movement, this conference will address a range of questions relating to the wealth of diplomatic, economic, intellectual and cultural encounters and exchange between 1945 – 1990, both within the Non-Aligned Movement, across the socialist world and with the developed countries. It will map the history of Yugoslavia’s global engagements not only as a subject associated with political and diplomatic

history, but also as a broader societal and cultural project.

This is a collaborative conference between ourselves and the Centre of Southeast European Studies at the University of Graz.

WHERE:

University of Graz

Meerscheinschlössl / Festsaal

Mozartgasse 3

8010 Graz

→University of Graz campus map

WHEN:

29 September 16:00 – 19:00 1 October

KEYNOTE SPEAKERS:

Professor Kristen Ghodsee

Professor Kristen Ghodsee

Bowdoin University, USA

Professor James Mark

Professor James Mark

University of Exeter & 1989 after 1989, UK

[Top]

Human Rights after 1945 Conference Report Published

Posted on 29 June, 2016 in1989 after 1989 Eastern Europe Globalisation Human Rights Post Socialism Rethinking 1989 Socialism

The conference Human Rights after 1945 in the Socialist and Post-Socialist World took place on the 3 – 5 March 2016 at the German Historical Institute, Warsaw. It was a collaborative conference between 1989 after 1989; the German Historical Institute Warsaw; Georg-August University of Göttingen and the London School of Economics. The aim of the conference was to highlight the role and historical agency of the socialist world in the history of human rights.

The conference report is now available on our conference pages and on Geschichte Transnational. It summarises papers presented across 6 panels covering topics such as state socialism, human rights and globalisation; how human rights is defined internationally; state socialist conceptualisation of rights and human rights; socialist foreign policy; transnational movements and flows; and political dissent in relation to the global history of human rights.

The importance of analyzing vernacular human rights, i.e. analyzing when and how people used human rights languages [5], was one of the leitmotifs of the conference. The issue of teleology and normativity in historical human rights research was another major topic. Consequently, many papers presented stories of failures that contradict positivist narratives and challenge policy-orientated narratives of democratic transition. Parallel to transnational and international human rights history, the role of the state in human rights history was another key issue of the conference. Bringing the state back in, human rights can also be seen as an element of legal history – a promising approach embedding the highly normative notion of human rights in a wider legal history context. This conference brought together scholars working on various regions and actors in a truly fruitful manner. It linked different approaches and perspectives on the history of human rights in a way that contributed to an urgently needed, more complex understanding of the socialist world’s role in human rights history.

Read the full conference report.

[Top]Global Circuits of Expertise and the Making of the Post-1945 World

Posted on 29 March, 2016 in1989 Cold War East Asia Eastern Europe Economy Hungary Post Socialism Rethinking 1989 Socialism

Interested in learning more about Professor James Mark’s research on Hungary, South Korea and economic exchange in the Late Cold War? Then why not come along to Global Circuits of Expertise and the Making of the Post-1945 World: Eastern European and Asian Perspectives in New York, 29 – 30 April 2016:

Location:

Weatherhead East Asian Institute

International Affairs Building, Room 918 – 420 West 118th Street, New York, New York 10027

Register:

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/global-circuits-of-expertise-and-the-making-of-the-post-1945-world-tickets-22426838277

This workshop aims to explore transfer and circulation of expert knowledge across socialist worlds in the post-1945 period of decolonization. The workshop brings together scholars with regional expertise, Eastern European and/or Asian, to seek commonalities between histories and historiographies that cut across regions, geopolitical blocs and continents.

Bringing these stories together, we will tell a story of expert circulation in the “socialist world.” These were regions where socialism was the dominant state ideology, where socialist parties were politically dominant, or where “progressive” export cultures played important roles. Yet we also wish to consider how experts from “socialist cultures” interacted globally, and were part of broader transnational debates over modernisation, political development, technology, and decolonization. Connections were made, for example, between Eastern Europe and India, as well as Socialist China and India, that defied Cold War blocs. Bringing scholars working across these regions, and on the place of these regions in a global perspective, will help provide important new insights into non-western contributions to various fields of knowledge in the wake of decolonisation.

This event is sponsored by the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, The Harriman Institute, and The Center for Science and Society at Columbia University, and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (UK)-funded research project “Socialism Goes Global”.

Workshop Programme

Friday, April 29

9:30 a.m. – 12:00 p.m.

Panel 1: Science and Decolonization

Chaired by Eugenia Lean, Columbia University

Session 1: The Eastern European Peasant in Nehru’s India: Transnational Debates on Rural Economies, 1930s-1960s

Malgorzata Mazurek, Columbia University

Session 2: Water Management and Transnational Expertise in 1950s China and India

Arunabh Ghosh, Harvard University

Session 3: Curing Ills with Socialist Medicine: China’s Medical Missions in Algeria, 1963-1973

Dongxin Zou, Columbia University

2:00 p.m. – 3:30 p.m.

Panel 2: Global Revolution: Circuits of Expertise and Techniques

Chaired by James Mark, Exeter University

Session 4: The Screen is Red: China and East Germany Make Films Together in 1950s

Quinn Slobodian, Wellesley College

Session 5: Between Work and Struggle: The Varieties of Bolshevik “Self-Criticism” in Maoist China

Chris Chang, Columbia University

3:45 p.m. – 5:00 p.m.

Panel 3: Politics of Exchange and Circulation

Chaired by Eugenia Lean, Columbia University

Session 6: Tending the Trees of Friendship, Breeding New Knowledge at Home: The Case of the Albanian Olive Tree in China

Sigrid Schmalzer, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Session 7: Earthquakes, Disaster Governance, and Socialist China — an International Perspective

Fa-ti Fan, State University of New York, Binghamton

Saturday, April 30

9:30 a.m. – 12:00 p.m.

Panel 4: Late Socialist Reforms: Economics and Exchange

Chaired by Malgorzata Mazurek, Columbia University

Session 8: Entangled Electronics: Bulgarian Computers and the Developing World as a Space of Exchange, 1967-1990

Victor Petrov, Columbia University

Session 9: The Political-Economy of Détente: Interdependence, Technocratic Internationalism and Formation of Perestroika Political Economy

Yakov Feygin, University of Pennsylvania

Session 10: Between Eastern Europe and the ‘East Asian Tigers’: Hungary, South Korea and Economic Exchange in the Late Cold War

James Mark, Exeter University

2:00 p.m. – 4:00 p.m.

Roundtable

Paul Betts, Oxford University

Eugenia Lean, Columbia University

Elidor Mehilli, Hunter College

Adam Tooze, Columbia University

Link to Conference Poster

[Top]Call for Papers: (Re)Thinking Yugoslav Internationalism – Cold War Global Entanglements and their Legacies

Posted on 14 December, 2015 in1989 after 1989 Cold War End of Yugoslavia Globalisation Rethinking 1989 Socialism

Graz, Austria

Centre for Southeast European Studies, University of Graz and the University of Exeter

30 September – 1 October 2016

Call for Papers Deadline: 28 February 2016

(Re)Thinking Yugoslav Internationalism – Cold War Global Entanglements and their Legacies

For more than forty years, Yugoslavia was one of the most internationalist and outward looking of all socialist countries in Europe, playing leading roles in various trans-national initiatives – principally as central participant within the Non-Aligned Movement – that sought to remake existing geopolitical hierarchies and rethink international relations. Both moral and pragmatic motives often overlapped in its efforts to enhance cooperation between developing nations, propagate peaceful coexistence in a divided world and pioneer a specific non-orthodox form of socialism.

Although the disintegration of socialist Yugoslavia has received extensive treatment across a range of disciplines, the end of Yugoslavia’s global role and the impacts this had both at home and abroad, have received little attention. Coinciding with the 55th anniversary of the Belgrade summit and the foundation of the Non-Aligned Movement, this conference seeks to open up a range of questions relating to the wealth of diplomatic, economic, intellectual and cultural encounters and exchange between 1945 – 1990, both within the Non-Aligned Movement, across the socialist world and with the developed countries. It would map the history of Yugoslavia’s global engagements not only as a subject associated with political/diplomatic history, but also as a broader societal and cultural project. Important witnesses involved in those exchanges and alliances will also be invited to share their experiences.

We welcome papers from different disciplines and from diverse perspectives, whether dealing with aspects of Cold War international cooperation, development, Yugoslavia’s global role, or the ‘global’ Cold War from the perspective of the developing world and the ‘global South’. We particularly encourage proposals which would reflect on:

- the roots of Yugoslav internationalism and how it was understood in cultural/economic/social as well as political/diplomatic terms;

- the contours of Yugoslav diplomacy and the ways Yugoslav elites conceptualised their global role;

- the role of Yugoslavia in the United Nations, its agencies and other international organisations as the fora for global encounters and in particular the attempts at tackling global inequality and alternative development;

- the relationship between Yugoslavia, the different liberation movements and the newly emerging independent nations in the ‘global South’ (including cultural diplomacy, labour migration, individual travel);

- the realities and challenges of foreign trade, investment construction and economic cooperation;

- the ways international engagements reshaped aspects of political, economic or cultural life back in Yugoslavia;

- the role and significance of the Non-Aligned Movement during the Cold War and today;

- the international impact of the end of Yugoslavia and the collapse of her global role;

- the legacies and new understandings of Yugoslavia’s global role.

Abstracts of 300-500 words, together with an accompanying short biographical note should be submitted to Natalie Taylor (N.H.Taylor@exeter.ac.uk) by 28 February 2016.

Funding opportunities for travel and accommodation are available, but we ask that potential contributors also explore funding opportunities at their home institutions.

This event is kindly supported by the Centre for Southeast European Studies and the Leverhulme Trust-funded project 1989 after 1989: Rethinking the Fall of State Socialism in Global Perspective at the University of Exeter.

[Top]Contested Nazi Victimhood after 1989

Posted on 23 September, 2015 in1989 Communism Fall of the Berlin Wall Memory Post Socialism Post-Soviet Countries Rethinking 1989 Socialism

By Nelly Bekus

International Day of Liberation of Nazi Concentration Camp Inmates and its Geopolitical Implications

The date 11th of April is marked by the Russian News Agency RIA as “International Day of Liberation of Nazi Concentration Camp Inmates.” According to RIA, “The International Day of Liberation was established to commemorate the international uprising of the Buchenwald concentration camp prisoners.” The Calendar of Events project—Calendar.ru, the most comprehensive resource on “holidays and memorial days” on Russian-language Internet, refers to April 11 as International Day of Liberation of Nazi Concentration Camp Inmates in two categories: in “Great Patriotic War” and as “International Days of Observance.” There is an article on this Day of Observance in Russian Wikipedia; it refers to RIA as a main source and even mistakenly claims that it was established by the UN. Information on International Day of Liberation of Nazi Concentration Camp Inmates, however, is not to be found in other languages anywhere except the Russian international news agency Sputnik, working in foreign languages (previously known as The Voice of Russia).

The piece of information provided by RIA serves as a starting point for hundreds of publications across the Russian and post-Soviet media that report on various remembrance events dedicated to the memory of victims of Nazi’s concentration camps taking place on this day. In Moscow, a memorial rally at Poklonnaya Hill is held at The Tragedy of the Peoples monument, erected in 1996 in the memory of former Nazi concentration camps’ inmates and constitutes an integral part of the Victory Memorial Park on Poklonnaya Hill in Moscow. Rallies are traditionally organized by the International Union of Former Juvenile Prisoners of Fascism. The Union was created in 1988 as the Union of Former Juvenile Prisoners in Soviet Union; in 1992 it was reinvented as the International Union, which provided platform for cooperation between analogous national Unions within the former Soviet space. In fact, the April 11 has been observed in those states, where national and local branches of this International Union function. Attended by former Nazi concentration camp inmates and their descendants these memorial meetings have profound public appeal due to the engagement of educational and cultural institutions and media coverage. Commemorations on the April 11 have been widely supported by local government; ceremonies are attended by top officials, with the exception of Baltic countries, where the remembrance events on the April 11 are supported by Orthodox Church instead.

Alongside the rallies, there are traditional ceremonies of flower-laying at the monuments and memorial sites dedicated to the former Nazi camps’ prisoners held across the regions, and also concerts in memory of victims, “lessons of heroism” at schools, various dedicatory exhibitions and meetings in public libraries and museums are organized across Russia and other post-Soviet states. Governmental educational resources provide variety of supporting materials such as proposed scenario for the “lessons on heroism,” suggested literature, etc. In a way, this informational support is analogous to what can be found on the United Nations webpage with educational materials and information products recommended for the observance of the International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust on the January 27, established by UN in 2006. In fact, the status of April 11 in post-Soviet countries clearly creates the impression of maintaining a parallel memory on the former inmates of Nazi’s concentration camps.

Between Auschwitz and Buchenwald

The symbolism of the date—the day of liberation of Buchenwald camp on April 11, as opposed to January 27, the day of liberation of the Camp of Auschwitz chosen by UN—appears to have special meaning in commemoration of victims of Nazi regime. This symbolism goes back to the initial stage of memorial work in the early post-war years. The history of the Buchenwald’s liberation compiled by RIA agency and reproduced every year in numerous post-Soviet media on the April 11 tells the story of heroic uprising of the Buchenwald concentration camp inmates:

“65 years ago, on April 11, 1945, a red flag was hoisted over the Buchenwald camp administrative building. On that day the inmates disarmed and took prisoner more than 800 SS-men and camp guards […]

Two days later US troops reached Buchenwald.”

This concise story mentions only shortly “the red flag” raised by underground rebels and fails to mention that the resistance was organized mostly by Communists. Similarly politically neutral narration can be found on the webpage of Buchenwald Museum: “April 11. The SS flees, but before the fighting is over, inmates of the camp resistance occupy the tower and take charge of order and administration in the camp.”

Evidently, communists’ involvement in the underground resistance at Buchenwald lost its appeal in contemporary perspective. Nevertheless, immediately after the war this fact was not only recognized but also effectively used in promotion of corresponding memory narrative on the struggle of communist antifascists against Nazis. The camp was perceived as a symbol of political victims who were also heroic fighters and played essential role in memorialization of the Second World War among anti-fascist in many European countries. Buchenwald’s key role in the formation of international memory of former concentration camps’ inmates was officially confirmed in 1948, when the International Federation of Former Political Prisoners (FIAPP) declared the April 11 as “The International Day of Former Political Prisoners” and “The International Day of the Deportees.” Later it was renamed into the “Day of International Solidarity of Liberated Political Prisoners and Fighters” by the successor of FIAPP—International Federation of Resistance Fighters (FIR). In those days, April 11 was a day with profound international anti-fascist connotation, which could be proudly communicated across the East-West divide. With the beginning of Cold War and the rising tensions between the Western and Eastern blocs, the political prisoners’ organization, such as FIAPP/FIR, lost their influence in the West. Buchenwald memory and the symbolism of April 11 were gradually reduced to the communist milieu.

In GDR, Buchenwald was entitled the role of major pantheon to heroic resistance fighters and the “self-liberation” of the camp became the focus of a memorial complex (1958). Buchenwald, a site of official pilgrimage and ceremonies, stood for antifascism and to some extent was called to instil pride. Memory narrative developed on the Eastern side of the Iron Curtain, which preferred to commemorate Communist “fighters” rather than Jewish “victims.” On the other side of the Berlin Wall, the association between communist ideology and post-war antifascist discourse in communist countries resulting in the marginalization of Holocaust made it easier for Western Allies to listen to the voice of victims of racial persecution, above all Jews. For them, it was Auschwitz that became the symbol of Nazi crimes as well as collective shame and guilt.

In the context of Cold War, the politicization of memorial work on the other side of the Iron Curtain was combined with the corresponding political line. Communist states combined it with anti-Western political propaganda; the Alliance and other anti-communist organizations merged honoring of Nazism’s victims with the pursuit of their own political agenda: comparing Stalinism with Nazism did more than condemn Communism; it also downplayed the uniqueness of the Nazis’ regime.

It was at that time, in 1950, when also the term “victims of fascism” was discarded by Philipp Auerbach for its communist connotations and proposed to replace it with “victims of Nazism.” Since then, the previously common enemy was even to be named by former Allies differently.

After 1989: An Unsuccessful Memory Unification

The Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 brought a hope that the memory of World War II could provide a solid ground for overcoming Cold War’s divisive legacy. In the 1990s it seemed fairly possible that integration of the “Western” and the “Eastern” perspectives into a common paradigm of remembering could become one of the building bricks in a new European home.

Some changes in the memory politics of the post-Soviet Russia and CIS countries have, indeed, occurred. The memory of Jewish genocide was given more consideration as a part of war story in the territory of former Soviet Union than previously. The real unification of European and post-Soviet memory spaces, however, has never been achieved. Instead, political transition in former socialist states and the reconfiguration of EU borders resulted in a formation of new symbolic mapping of memory.

In the European history of remembering the victims of the Second World War, the focus on Holocaust was transformed, as Aleida Assmann noted, “into a transgenerational and transnational memory.” Shared memories of Holocaust were capable of uniting European countries in commemorating its victims and teaching next generation of Europeans the history lesson, becoming a foundation myth for united Europe and a moral yardstick for new member states since 2005. Commemoration of the Holocaust victims came to be one of unifying rites called to manifest the common efforts in creation of Europe as a remembering community. In 2005, European Holocaust Memorial Day across the EU was established on January 27. The same year and for the same date the General Assembly of UN established annual International Day of Commemoration in Memory of Victims of the Holocaust. Even though in some calendars of several former socialist states one can still find “Day of International Solidarity of Liberated Political Prisoners and Fighters” mentioned with the reference to Buchenwald liberation, no commemorative activity has ever been reported on this day outside post-Soviet space.

Many post-Soviet countries also join UN commemorations of the Holocaust victims. None of them, however, has the Commemoration Day included into the official calendar of observance days. In Russia and other post-Soviet countries this day has been observed by Jewish national organizations, foreign diplomatic missions and has, as a rule, semi-official status. Several attempts have been made to include commemoration of Holocaust into the official calendar of Russian state which has considerable Jewish community: in 2001, by the foundation “Holocaust”; in 2008 by the Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia; in 2012 by the Russian Jewish Congress; in 2013 by a Russian opposition party “Just Russia.” None of these initiatives, however, has been successful.

The day of 27th of January has been widely commemorated by national and religious Jewish organizations of Russia, often with the participation of Russian top officials. The president of Russia often takes part in these observances, but the mode and the context of such commemoration clearly marks the space of the Holocaust memory as a matter of one of Russia’s religious and national minorities. In 2010, Dmitry Medvedev, the then President of Russia, sent his greetings to participants in the ceremonies commemorating the 65th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. In his address, Medvedev urged not forget that along with six million people that “were killed simply because of their ethnicity, simply for being Jewish,” there were other victims, too, because “according to the Nazis’ plan, at least a third of the population in the occupied territories was to follow their fate.” This attention to “other victims” of Nazi’s genocide in Medvedev’s address, as well as keeping the status of International Holocaust Remembrance Day as a matter of one of Russian Federation’s national minorities reveal an unarticulated intention to keep the weight of the “Jewish aspect” in the post-Soviet memory of the Second World War under controlled balance. It displays the post-Soviet determination to prevent total re-writing of the Soviet-originated narrative of the history of Second World War and the re-casting the memory on its victims in accordance with “Western” mode. And while Jewish communities in Russia join worldwide commemoration of January 27 as International Holocaust Remembrance Day, in the calendar of Russian state, January 27 is also marked as a date commemorating the end of Leningrad siege (established in 1995).

Reshaping a Divided Victimhood

Surely, in contemporary conditions the division lines in the memory sphere work differently. Disregarding Holocaust in post-Soviet countries proves to be both impossible and unreasonable and Jewish communities across the former Soviet space observe the Memory of Holocaust on January 27. Emphasis on Holocaust, however, conveys implicit meaning of being “Western interpretation” of Nazi’s victimhood. And revitalization of public commemorations on April 11 in post-Soviet states clearly demonstrates that the once envisaged “unification” of divided victimhood is not going to be achieved by one-sided acceptance of the “Western” memory perspective by the former “East”. Along with the “Europeanization of the memory boom” denoted by rising significance of Holocaust Remembrance Day on January 27, the official memory politics in post-Soviet countries sought to establish alternative commemoration which would meet the needs and wishes of the majority of former Soviet people. April 11 was assigned this role of the post-Soviet parallel to the European Commemoration of Holocaust which allows to maintain “other” perspective on the “victimhood of fascism” alongside the memory of Holocaust. Buchenwald as a symbolic alternative came almost naturally to fit this new memory practice demand. Buchenwald camp was widely known to the Soviet people. Due to a popular patriotic song “Buchenwald alarm bells,” it was part of the official canon of the Soviet cultural war memory.

April 11 reiterates in many respects the idea of commemoration of Holocaust victims—but it avoids stressing the ethnic genocide of Jews or any other particular ethnic group. Every publication on commemoration of the Liberation of Nazi Concentration Camp Inmates speaks, instead, about 5 million of Soviet people among 19 million of Nazi camps’ prisoners; in some cases, 6 million of Jewish victims are mentioned, too.

On the one hand, recalling the memory of the Soviet victims among prisoners of Nazi’s concentration camps in public commemorations and rituals held on the April 11 can be read as the efforts to maintain post-Soviet space as a “remembering community.” On the other hand, persistent emphasis on the international status of this day is also telling. Nations that once belonged to USSR today represent international community aspiring to be an actor on the geopolitical memory arena. At the same time, talking about any long-established history of April 11 as an International Day of observance refers to the “internationalism” characteristic for post-war political anti-fascism and resistance fighters. And while communist ideology that once constituted the core of that movement became irrelevant and marginal, its internationalist appeal remains meaningful. Bridging these two aspects in the commemorative practices on April 11 makes possible the prevention of the post-Soviet space of commemoration of victims from segregation and isolation, at least symbolically.

This relatively new memorial date can be interpreted as a signifier in the geopolitics of memory coming to replace political ideologies, which constituted inseparable feature of the memorial work in the Cold War realm. It shows how geopolitical entities have been re-constituted and united anew, while the process of re-shaping memories attendant upon the end of Cold War remains embedded in the divisions of the past.

Original is published by Aspen Review

http://www.aspeninstitute.cz/en/article/3-2015-contested-nazi-victimhood-after-1989/

[Top]Global Socialism and Post Socialism Workshop Report

Posted on 8 July, 2015 in1989 after 1989 Globalisation Post Socialism Rethinking 1989 Socialism

Held May 13, 2015 at The University of Exeter

Report by James Mark, Nelly Bekus, Anna Calori, Raluca Grosecu, Ned Richardson-Little, and Ljubica Spaskovska

While the topic of globalization has emerged as rapidly growing field in recent years, the role of the socialist world is often neglected or seen as passive or unengaged in these processes. This workshop, hosted by 1989 after 1989: Rethinking the Fall of State Socialism in Global Perspective research group, sought to challenge these narratives by examining the myriad engagements of the socialist world with the global. The presentations proposed new methodological and theoretical means of grappling with how late socialism fits into the larger narrative of globalization, examined the spaces in which processes of globalization occurred in the socialist world, and analyzed the long-term effects of these developments after 1989 and the collapse of state-socialism.

Tobias Rupprecht (University of Exeter) opened the first panel – Approaches to Globalisation and The Socialist World – providing a broad introduction to the themes of the workshop. He explored how current literature on globalisation is still often shaped by the values of the 1990s, and how, within this, the socialist world is most commonly presented simply as a victim of globalising forces. He then demonstrated the various ways in which the socialist world provided templates for ‘alternative globalisations’, and also acted as co-producer of some of the aspects of the globalised world we experience today.

Tobias Rupprecht (University of Exeter) opened the first panel – Approaches to Globalisation and The Socialist World – providing a broad introduction to the themes of the workshop. He explored how current literature on globalisation is still often shaped by the values of the 1990s, and how, within this, the socialist world is most commonly presented simply as a victim of globalising forces. He then demonstrated the various ways in which the socialist world provided templates for ‘alternative globalisations’, and also acted as co-producer of some of the aspects of the globalised world we experience today.

Bogdan Iacob (New Europe College, Bucharest) presentation – Negotiating the National. Romania, Globalization, and International Congresses of Historical Sciences (1970-1980) – analysed the responses of the Romanian socialist government to the rising web of interdependencies in 1970s, which would come to be known as globalization in the next decade. He then tested the implementation of this position for the case of the country’s engagement with International Congresses of Historical Sciences, particularly those between 1970 and 1980 – in Moscow, San Francisco, and Bucharest. Focusing on the Bucharest conference of 1980, the Iacob argued that one can identify a dichotomous approach to globalization in the case of Romania. On the one hand, the country was fully engaged with supra-, inter-, and non- governmental institutions during the global Cold War. On the other hand, the internationalization of Romanian state socialism also meant showcasing components of local modernity. The presentation underlined that the Romanian case of socialism going global is a cautionary tale. It is the story of a regime engrossed in the global encounters of the 1960s and 1970s that reaches, in 1980s, a final phase of systemic insulation and exacerbated essentialism. For the local, state socialist globalization ultimately meant carving pericentric frameworks highly dependent into very specific Cold War contexts.

Bogdan Iacob (New Europe College, Bucharest) presentation – Negotiating the National. Romania, Globalization, and International Congresses of Historical Sciences (1970-1980) – analysed the responses of the Romanian socialist government to the rising web of interdependencies in 1970s, which would come to be known as globalization in the next decade. He then tested the implementation of this position for the case of the country’s engagement with International Congresses of Historical Sciences, particularly those between 1970 and 1980 – in Moscow, San Francisco, and Bucharest. Focusing on the Bucharest conference of 1980, the Iacob argued that one can identify a dichotomous approach to globalization in the case of Romania. On the one hand, the country was fully engaged with supra-, inter-, and non- governmental institutions during the global Cold War. On the other hand, the internationalization of Romanian state socialism also meant showcasing components of local modernity. The presentation underlined that the Romanian case of socialism going global is a cautionary tale. It is the story of a regime engrossed in the global encounters of the 1960s and 1970s that reaches, in 1980s, a final phase of systemic insulation and exacerbated essentialism. For the local, state socialist globalization ultimately meant carving pericentric frameworks highly dependent into very specific Cold War contexts.

The second panel – The Socialist World, Trade, and Globalisation – began with James Mark’s  (University of Exeter) presentation, “Between the Eastern Bloc and the East Asian ‘Tigers’: The Opening Up between Hungary and South Korea 1970-1995.” Mark used the opening up between Hungary and South Korea to explore the ways in which experts in a socialist state imagined the operation of the world economy in the late Cold War. He showed how reform economists in Hungary, influenced by World Systems Theory, re-imagined their country’s role in the world economy as semi-peripheral. This then led them to an interest in the Asian “Tigers” as examples of successful integration into the world economy by formerly semi-peripheral countries. He explored these experts’ new prescriptions for the Hungarian economy from this perspective, and the fascination with South Korea amongst political and economic elites in the last years of state socialism.

(University of Exeter) presentation, “Between the Eastern Bloc and the East Asian ‘Tigers’: The Opening Up between Hungary and South Korea 1970-1995.” Mark used the opening up between Hungary and South Korea to explore the ways in which experts in a socialist state imagined the operation of the world economy in the late Cold War. He showed how reform economists in Hungary, influenced by World Systems Theory, re-imagined their country’s role in the world economy as semi-peripheral. This then led them to an interest in the Asian “Tigers” as examples of successful integration into the world economy by formerly semi-peripheral countries. He explored these experts’ new prescriptions for the Hungarian economy from this perspective, and the fascination with South Korea amongst political and economic elites in the last years of state socialism.

With his presentation, “Trading Internationalism: Rethinking Cold War Narratives through Sino-Middle East Relations, 1950s-70s,” Sam Zhiguang (University of Exeter) challenged the idea that international trade should be conceptualized solely in terms of commercial value. He argued that both Western economic models of comparative advantage or concepts such as Socialist division of labour did not capture the ideological and cultural meaning of trade in the People’s Republic of China during the Cold War. According to Chinese doctrine, establishing international unity was essential to national unity. One of the key means of fostering solidarity with the Third World was through the exchange of trade delegations. Through the lens of Sino-Middle East relations, he contended that while these exchanges did not often lead to significant commercial activity, this was not their primary goal. Chinese enthusiasm for engagement with the Middle East was not motivated by profit, but a more complex ideological understanding of global unity as a proxy for the wellbeing of China itself under Communist rule.

Anna Calori’s (PhD student, University of Exeter) presentation titled “Privatisation Reforms and the Global Market: Fragmenting the Workforce in Late-Socialist Bosnia-Hercegovina” explored the rationale behind the late 1980s economic reforms in Yugoslavia and their disruptive effects within the workplace of large, exporting companies. Engaging with primary sources such as factory bulletins and internal journals, Calori provided an analysis of discourses and debates around what was presented as a necessary change in the Yugoslav economic model of workers’ self-management. Responses to the urgencies of competitiveness on the global market meant a re-conceptualisation of the (post) socialist worker based on new exclusionary categories of merit and efficiency. This deeply affected the industrial workplace, exacerbating the already existing skills divisions and allowing for a further fragmentation of the workforce in the critical moments leading to Yugoslavia’s disruption.

Calori’s (PhD student, University of Exeter) presentation titled “Privatisation Reforms and the Global Market: Fragmenting the Workforce in Late-Socialist Bosnia-Hercegovina” explored the rationale behind the late 1980s economic reforms in Yugoslavia and their disruptive effects within the workplace of large, exporting companies. Engaging with primary sources such as factory bulletins and internal journals, Calori provided an analysis of discourses and debates around what was presented as a necessary change in the Yugoslav economic model of workers’ self-management. Responses to the urgencies of competitiveness on the global market meant a re-conceptualisation of the (post) socialist worker based on new exclusionary categories of merit and efficiency. This deeply affected the industrial workplace, exacerbating the already existing skills divisions and allowing for a further fragmentation of the workforce in the critical moments leading to Yugoslavia’s disruption.

In the third panel, “Spaces of Globalisation in Eastern Europe” Ljubica Spaskovska (University of Exeter) examined “Socialist global citizenship: the case of Yugoslavia.” Spaskovska’s presentation addressed a range of “spaces” of global encounters and cooperation through the lens of “global citizenship.” In different ways related to the United Nations, the Non Aligned Movement, the International Centre for Public Enterprises in Developing Countries and the post-1963 earthquake development plan for Skopje were some of those spaces of global citizenship where ideas that revolved around (equitable) development, anti-colonialism, fairer terms of trade and fostering ‘active peaceful coexistence’ gained ground. Socialist Yugoslavia’s “globally imagined citizenship” was a chartered foreign policy course that produced an impressive record of economic, intellectual and cultural exchange and enabled the country to vie for influence and recognition in a divided world. Although often discordant, the Non Aligned Movement managed to carve out alternative spaces and put forward novel development agendas and paradigms of international cooperation.

In the third panel, “Spaces of Globalisation in Eastern Europe” Ljubica Spaskovska (University of Exeter) examined “Socialist global citizenship: the case of Yugoslavia.” Spaskovska’s presentation addressed a range of “spaces” of global encounters and cooperation through the lens of “global citizenship.” In different ways related to the United Nations, the Non Aligned Movement, the International Centre for Public Enterprises in Developing Countries and the post-1963 earthquake development plan for Skopje were some of those spaces of global citizenship where ideas that revolved around (equitable) development, anti-colonialism, fairer terms of trade and fostering ‘active peaceful coexistence’ gained ground. Socialist Yugoslavia’s “globally imagined citizenship” was a chartered foreign policy course that produced an impressive record of economic, intellectual and cultural exchange and enabled the country to vie for influence and recognition in a divided world. Although often discordant, the Non Aligned Movement managed to carve out alternative spaces and put forward novel development agendas and paradigms of international cooperation.

In Ned Richardson-Little’s (University of Exeter) paper “Where the World Meets”: Globalization and Socialism at the Leipzig Trade Fair,” he examined the paradoxes of East Germany’s engagement with the world through the lens of famous Leipziger Messe. While the trade fair was supposed to serve as a site of cooperation fostering East-West understanding and exchange between “the two world systems,” it was also to serve as the “show-window of socialism” and demonstrate the superiority of the Socialist Bloc over its Western counterparts. The Trade Fair initially acted as a proxy site of diplomatic and cultural contact with the world while East Germany remained diplomatically unrecognized outside the Socialist Bloc. Later, the Trade Fair acted as a crucial venue for GDR efforts to integrate into the modernizing global economy in the 1970s and 1980s through joint ventures with the West and Third World export deals. While the Trade Fair was a gateway to the benefits of globalization, it was also a site of dangerously uncontrolled contact for East Germans to the outside world, which contributed to the political destabilization of the 1980s.

In Ned Richardson-Little’s (University of Exeter) paper “Where the World Meets”: Globalization and Socialism at the Leipzig Trade Fair,” he examined the paradoxes of East Germany’s engagement with the world through the lens of famous Leipziger Messe. While the trade fair was supposed to serve as a site of cooperation fostering East-West understanding and exchange between “the two world systems,” it was also to serve as the “show-window of socialism” and demonstrate the superiority of the Socialist Bloc over its Western counterparts. The Trade Fair initially acted as a proxy site of diplomatic and cultural contact with the world while East Germany remained diplomatically unrecognized outside the Socialist Bloc. Later, the Trade Fair acted as a crucial venue for GDR efforts to integrate into the modernizing global economy in the 1970s and 1980s through joint ventures with the West and Third World export deals. While the Trade Fair was a gateway to the benefits of globalization, it was also a site of dangerously uncontrolled contact for East Germans to the outside world, which contributed to the political destabilization of the 1980s.

The fourth panel on “Global Socialism and Its Legacies” began with Raluca Grosescu (University of Exeter) presenting on “International Criminal Law Before and After 1989: The Case of the UN Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity.” Grosescu examined the role of state-socialist countries in the development of international criminal law, through the example of the 1968 UN Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity. She examined the context, the negotiations, and the interpretations that had been given to the Convention in 1968 and then focused on the Convention’s application and its new readings in domestic prosecutions of human rights abuses in Argentina and Estonia in the 2000s. Grosescu argued that international criminal law norms initiated or supported by state-socialist countries during the Cold War have been highly instrumental in trials dealing with crimes of authoritarian regimes during the “third-wave of democratization” in Latin America and Eastern Europe. The presentation also reflected on the historicity of law by examining how legal norms constructed in a particular historical context with a specific political purpose are re-interpreted and re-negotiated in order to fulfil new political goals in the present.

The fourth panel on “Global Socialism and Its Legacies” began with Raluca Grosescu (University of Exeter) presenting on “International Criminal Law Before and After 1989: The Case of the UN Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity.” Grosescu examined the role of state-socialist countries in the development of international criminal law, through the example of the 1968 UN Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity. She examined the context, the negotiations, and the interpretations that had been given to the Convention in 1968 and then focused on the Convention’s application and its new readings in domestic prosecutions of human rights abuses in Argentina and Estonia in the 2000s. Grosescu argued that international criminal law norms initiated or supported by state-socialist countries during the Cold War have been highly instrumental in trials dealing with crimes of authoritarian regimes during the “third-wave of democratization” in Latin America and Eastern Europe. The presentation also reflected on the historicity of law by examining how legal norms constructed in a particular historical context with a specific political purpose are re-interpreted and re-negotiated in order to fulfil new political goals in the present.

In her presentation on “Soviet Frames of Global Experience in Architecture, Before and After 1989,” Nelly Bekus (University of Exeter) argued that both architecture and urban planning were considered to be a powerful instrument in cold war politics. The presentation examined the specific frameworks of the concept of Soviet internationalism, which mentally mapped the world beyond the ideological blocs. Specific educational and professional conditions and practices elaborated for architects in the USSR meant to produce such mental representation of the Soviet Union territory that made it fully operational and sufficient for self-perception of Sovietness as a form of global identity. Bekus also discussed International Architectural Design competitions as a space of global engagement of architects beyond the Soviet borders. These competitions often served as stages of “global professionalism” for architects and in which Soviet participants could claim their part.

In her presentation on “Soviet Frames of Global Experience in Architecture, Before and After 1989,” Nelly Bekus (University of Exeter) argued that both architecture and urban planning were considered to be a powerful instrument in cold war politics. The presentation examined the specific frameworks of the concept of Soviet internationalism, which mentally mapped the world beyond the ideological blocs. Specific educational and professional conditions and practices elaborated for architects in the USSR meant to produce such mental representation of the Soviet Union territory that made it fully operational and sufficient for self-perception of Sovietness as a form of global identity. Bekus also discussed International Architectural Design competitions as a space of global engagement of architects beyond the Soviet borders. These competitions often served as stages of “global professionalism” for architects and in which Soviet participants could claim their part.

In opening the concluding discussion, Angela Romano (University of Glasgow) underlined the importance of combining a micro- and a macro perspective, which would in turn shed light on the range of networks and the contribution of the socialist world to the processes of globalisation. She emphasized the importance of re-integrating 1989 into the study of the alternative spaces of globalization – not necessarily as a turning point, but as an opening for the debate about different forms and practices of global engagements that shaped both the socialist and the post-socialist world.

Workshop Overview

Panel 1: Approaches to Globalisation and The Socialist World

Dr Tobias Rupprecht (Exeter), The ‘Socialist World’ and ‘Global History’

Bogdan C. Iacob (New Europe College, Bucharest), Politics of National Identity as Mechanism of Globalizing Late State Socialism

Panel 2: The Socialist World, Trade, and Globalisation

Professor James Mark (Exeter), Between the Eastern Bloc and the east Asian ‘Tigers’: The Opening Up between Hungary and South Korea 1970-1995

Dr Sam Zhiguang (Exeter), Trading Internationalism: Rethinking Cold War Narratives through Sino-Middle East Relations, 1950s-70s

Anna Calori (PhD, Exeter), Privatisation reforms and the global market: fragmenting the workforce in late-socialist Bosnia-Hercegovina

Panel 3: Spaces of Globalisation in Eastern Europe

Dr Ljubica Spaskovska (Exeter), Socialist Global Citizenship: The Case of Yugoslavia

Dr Ned Richardson-Little (Exeter), “Where the World Meets”: Globalization and Socialism at the Leipzig Trade Fair

Panel 4: Global Socialism and Its Legacies

Dr Raluca Grosescu (Exeter) International Criminal Law Before and After 1989: The Case of the 1968 UN Convention on War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity

Dr Nelly Bekus (Exeter) Soviet Frames of Global Experience in Architecture, Before and After 1989

Concluding Discussion

with comments from Dr Angela Romano (University of Glasgow)

[Top]