Programme now available for our conference on State Socialism, Heritage Experts and Internationalism

Posted on 20 October, 2017 inArea Studies Communism East Asia Eastern Europe End of Yugoslavia Globalisation Heritage Heritage Experts Latin America Memory Nation Building Post Socialism Post-Soviet Cities South Africa

State Socialism, Heritage Experts and Internationalism in Heritage Protection after 1945

21-22 November 2017

Location: Reed Hall, University of Exeter, UK

Join us for our conference exploring the rising contributions of socialist and non-aligned actors to the development of heritage at both domestic and international levels.

CONFERENCE SYNOPSIS

Histories of heritage usually perceive their object of study as a product of western modernity, and exclude the socialist world. Yet, understood as a cultural practice and an instrument of cultural power, and as a “right and a resource”, heritage has played important roles in managing the past and present in many societies and systems. In the postwar period, preservation became a key element of culture in socialist and non-aligned states from China, the Soviet Union, and the Eastern Bloc to Asia, Latin America and Africa. Attention paid to the peoples’ traditions and heritage became a way to manifest the superiority and historical necessity of socialist development. However, the contribution of socialist states and experts to the development of the idea of heritage is still to be fully excavated.

The conference aims to understand the rising contributions of socialist and non-aligned actors to the development of heritage at both domestic and international levels. This phenomenon was in part the result of country-specific factors – such as a reaction to rapid industrial development; the destruction of both the Second World War or wars of national liberation; and the necessity to (re)-invent national traditions on socialist terms. But it was also due the growth of a broader international consensus on international heritage protection policies – in which socialist and non-aligned states and their experts played an important role. To this end, the conference will also address the relationship between socialist conceptions of heritage and those found in the capitalist world: to what extent can we discern the convergence of Eastern and Western dynamics of heritage discourses and practices over the second half of the twentieth century? To what degree did heritage professionals from socialist states play a role in the formation of the transnational and transcultural heritage expertise? To what extent did heritage still play a role in Cold War competition? Socialist states claimed that their respect for progressive traditions and material culture distinguished their superior methods of development from that of the capitalist world. Non-Aligned countries often attempted to blend aspects of socialist and capitalist logics of cultural heritage politics.

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME

Day 1 – 21 November

08.45-09.15 Registration

09.15-09.30 Introduction

09.30-10.30 Panel 1: Transnational Circulations of Heritage Concepts and Ideas (Part 1)

Chair James Mark

Discussant Michael Falser

Nikolai Vukov (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences) Ethnographising the Past, Ideologising the Present: Traditional Heritage as an Ideological Resource and International Asset in Eastern Europe after 1945

Yao Yuan (Nanjing University) International Factors in Shaping Chinese Heritage Conservation Policy

10.30-10.45 Refreshment Break

10.45-12.00 Panel 1: Transnational Circulations of Heritage Concepts and Ideas (Part 2)

Chair Corinne Geering

Discussant Nelly Bekus

Marko Spikic (University of Zagreb) Between Exceptionalism and Internationalism: Ethics and Politics of the Conservation System in People’s Republic of Croatia of the 1950s

Pablo Gonzalez (University of Lisbon) A Rebel Heritage for the Cuban Revolution: Socialist Internationalism, Art and Soviet Influence

12.00-13.00 Keynote Lecture: Stephen Smith (University of Oxford) Heritage in Contention: the Soviet Union and China after 1945

13.00-14.30 Lunch

14.30-16.00 Panel 2: International Organisations and Socialist Heritage

Chair Kate Cowcher

Discussant Nikolai Vukov

Nelly Bekus (University of Exeter) Tracing Multiple Logics in Soviet Heritage-Making: Pan-Soviet, National and International Agencies of Cultural Power

Corinne Geering (Justus-Liebig-University Giessen) World Heritage beyond UNESCO: Soviet Approaches to World Heritage before 1988

Emanuela Grama (Carnegie Mellon University) International mediations: UNESCO visits to Romania at the end of the Cold War or heritage as a right to place

16.00-16.15 Refreshment Break

16.15-17.15 Panel 3: South East Asia and Socialist Heritage

Chair Natalia Telepneva

Discussant James Mark

Michael Falser (Heidelberg University – Université Bordeaux-Montaigne) Cold War and non-aligned heritage politics in South and South-East Asia

Alicja Gzowska (University of Warsaw) One man’s dream? Polish conservation experts in Vietnam

19.00 Drinks Reception – Devon and Exeter Institution

20.00 Conference Dinner – Rendezvous

Day 2 – 22 November

09.00 – 10.30 Panel 4: The Development of Socialist Ideas of Heritage in Africa (Part 1)

Chair Nelly Bekus

Discussant Paul Betts

Kate Cowcher (University of Maryland) Origin Myths and Incarcerations: Ethiopia’s National Museum amidst socialist revolution

Piotr Marciniak (Poznan University of Technology) From Warsaw to Faras. The Polish School of Reconstruction and Conservation of Monuments and Sites: People, Doctrine and History

Natalia Telepneva (University of Warwick) The Soviet-Somali Archaeological Expedition and the Global Struggle for the Horn of Africa

10.30-10.45 Refreshment break

10.45-11.45 Panel 4: The Development of Socialist Ideas of Heritage in Africa (Part 2)

Chair Michael Falser

Discussant Marko Spikic

Nadine Siegert (University of Bayreuth) (Re)activated heritage. State-sponsored socialist propaganda and architecture in the Luanda cityscape

Nina Díaz Fernández (University of Ljubljana) Yugoslav Experts and the Protection of Monuments in the Third world

11.45-13.00 Round Table

Paul Betts (University of Oxford)

Michael Falser (Heidelberg University – Université Bordeaux-Montaigne)

James Mark (University of Exeter)

13.00 Farewell Lunch

Conference Convenors:

Professor James Mark and Dr. Nelly Bekus, University of Exeter and 1989 after 1989

Professor James Mark and Dr. Nelly Bekus, University of Exeter and 1989 after 1989

Dr. Michael Falser, Cluster of Excellence Asia and Europe in a Global Context, Heidelberg University

Secret Agents and the Memory of Everyday Collaboration in Communist Eastern Europe

Posted on 17 October, 2017 in1989 Area Studies Communism Eastern Europe End of Yugoslavia GDR Hungary Memory Post Socialism Rethinking 1989 Romania

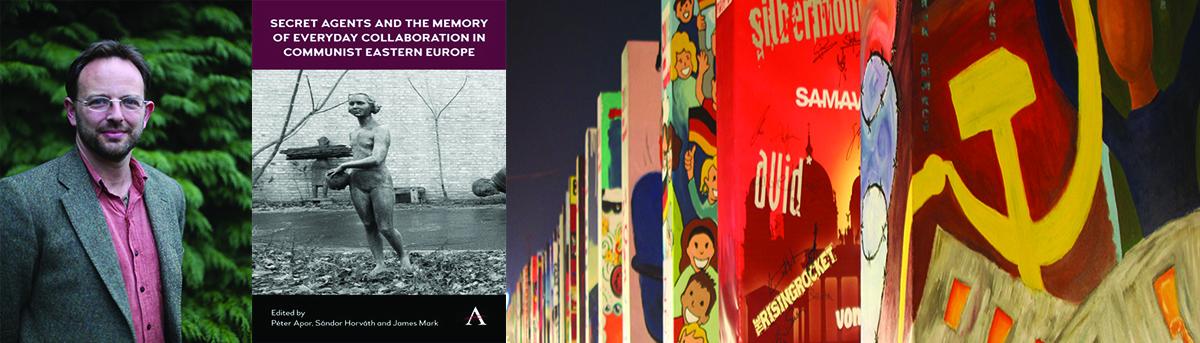

Professor James Mark’s co-edited volume Secret Agents and the Memory of Everyday Collaboration in Communist Eastern Europe is now available through Anthem Press.

Professor James Mark’s co-edited volume Secret Agents and the Memory of Everyday Collaboration in Communist Eastern Europe is now available through Anthem Press.

This collection of essays addresses institutions that develop the concept of collaboration, and examines the function, social representation and history of secret police archives and institutes of national memory that create these histories of collaboration. The essays provide a comparative account of collaboration/participation across differing categories of collaborators and different social milieux throughout East-Central Europe. They also demonstrate how secret police files can be used to produce more subtle social and cultural histories of the socialist dictatorships. By interrogating the ways in which post-socialist cultures produce the idea of, and knowledge about, “collaborators,” the contributing authors provide a nuanced historical conception of “collaboration,” expanding the concept toward broader frameworks of cooperation and political participation to facilitate a better understanding of Eastern European communist regimes.

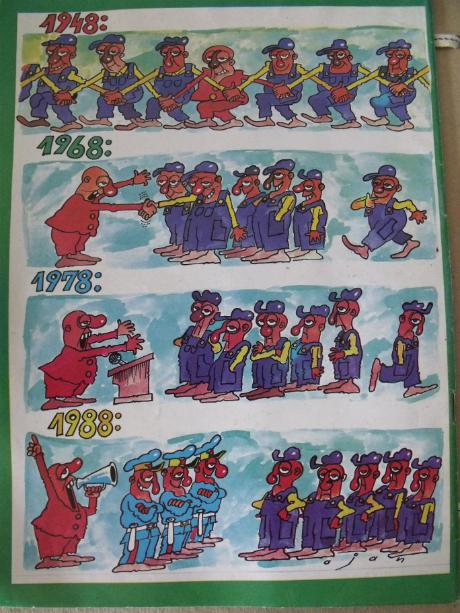

Edited by Péter Apor, Sándor Horváth and James Mark, the essays are framed into three parts – Institutes, Secret Lives and Collaborating Communities and include topics such as the Stasi Records of the former GDR; memory in Latvia, Slovak and the Czech Republics; Tito and intellectuals 1945-80; entangled stories with the Former Securitate; Regional-level Party Activists in Slovakia and priest collaboration in Slovak Catholic memory after 1989.

Edited by Péter Apor, Sándor Horváth and James Mark, the essays are framed into three parts – Institutes, Secret Lives and Collaborating Communities and include topics such as the Stasi Records of the former GDR; memory in Latvia, Slovak and the Czech Republics; Tito and intellectuals 1945-80; entangled stories with the Former Securitate; Regional-level Party Activists in Slovakia and priest collaboration in Slovak Catholic memory after 1989.

“This excellent volume marks a genuine breakthrough in our knowledge about the everyday lives of the people who made up the secret police, of their motivations and their experiences. It challenges binary visions of the past and powerfully highlights the complexity of the term ‘collaboration.’ Ultimately, it makes a case for the human factor in the history of the repressive state.”

Ulf Brunnbauer, Director, Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies, Regensburg, Germany

Table of Contents

Frameworks: Collaboration, Cooperation, Political Participation in the Communist Regimes

(The Editors)

Part 1: Institutes

Chapter 1: A Dissident Legacy, The ‘Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records of the Former GDR’ (BStU) in United Germany

(Bernd Schaefer)

Chapter 2: In Black and White? The Discourse on Polish Post-War Society by the Institute of Polish Remembrance

(Barbara Klich-Kluczewska)

Chapter 3: The Exempt Nation: Memory of Collaborationism in Contemporary Latvia

(Leva Zake)

Chapter 4: Institutes of Memory in the Slovak and Czech Republics – What Kind of Memory?

(Martin Kovanič)

Chapter 5: Closing the Past – Opening the Future. Hungarian Victims and Perpetrators of the Communist Regime

(Péter Apor and Sándor Horváth)

Chapter 6: To Collaborate and to Punish. Democracy and Transitional Justice in Romania

(Florin Abraham)

Part 2: Secret Lives

Chapter 7: ‘Resistance through Culture’ or ‘Connivance through Culture.’ Difficulties of Interpretation; Nuances, Errors, and Manipulations

(Gabriel Andreescu)

Chapter 8: Intellectuals between Collaboration and Independence. Politics and Everyday Life in the Prague Faculty of Arts in Late Socialism

(Matěj Spurný)

Chapter 9: Tito and Intellectuals – Collaboration and Support, 1945–1980

(Josip Mihaljević)

Chapter 10: Spy in the Underground. Polish Samizdat Stories

(Paweł Sowiński)

Chapter 11: Entangled Stories. On the Meaning of Collaboration with the Former Securitate

(Cristina Petrescu)

Part 3: Collaborating Communities

Chapter 12: Finding the Ways (around). Regional-level Party Activists in Slovakia

(Marína Zavacká)

Chapter 13: ‘But Who is the Party?’ History and Historiography in the Hungarian Communist Party

(Tamás Kende)

Chapter 14: Forgetting ‘Judas’. Priest Collaboration in Slovak Catholic Memory after 1989

(Agáta Drelová)

Chapter 15: Informing as Life-Style. Unofficial Collaborators of the Hungarian and the East-German State Security (Stasi) Working in the Tourism Sector

(Krisztina Slachta)

→ Order your copy through the Anthem Press website: Secret Agents and the Memory of Everyday Collaboration in Communist Eastern Europe

[Top]The “Children of Crisis”: Making Sense of (Post)socialism and the End of Yugoslavia

Posted on 24 July, 2017 in1989 1989 after 1989 End of Yugoslavia Generation Memory Post Socialism Socialism

Ljubica Spaskovska’s article The “Children of Crisis”: Making Sense of (Post)socialism and the End of Yugoslavia has just been published in the Journal of East European Politics and Societies, Volume 31, Issue 3, August 2017. It forms part of a special section on the Genealogies of Memory, guest edited by Ferenc Laczó and Joanna Wawrzyniak.

Ljubica Spaskovska’s article The “Children of Crisis”: Making Sense of (Post)socialism and the End of Yugoslavia has just been published in the Journal of East European Politics and Societies, Volume 31, Issue 3, August 2017. It forms part of a special section on the Genealogies of Memory, guest edited by Ferenc Laczó and Joanna Wawrzyniak.

Ljubica’s article traces certain mnemonic patterns in the ways individuals who belonged to the late-socialist Yugoslav youth elite articulated their values in the wake of Yugoslavia’s demise and the ways they make sense of the Yugoslav socialist past and their generational role a quarter of a century later. It detects narratives of loss, betrayed hopes, and a general disillusionment with politics and the state of post-socialist democracy that appear to be particularly frequent in the testimonies of the media and cultural elites. They convey a sense of discontent with the state of post-Yugoslav democracy and with the politicians—some belonging to the same generation—who embraced conservative values and a semi-authoritarian political culture. The article argues that an emerging new authoritarianism and the very process of progressive disillusionment with post-socialist politics allowed for the emergence and articulation of such alternative, noninstitutionalized individual memories that, whilst not uncritical of the Yugoslav past, tend to highlight its positive aspects.

→ East European Politics and Socieities, Volume 31, Issue 3, August 2017

[Top]Ljubica Spaskovska’s Monograph Now Available: The Last Yugoslav Generation

Posted on 24 May, 2017 in1989 after 1989 End of Yugoslavia Post Socialism Socialism Uncategorized

Manchester University Press have now published Dr Ljubica Spaskovska‘s new book – The Last Yugoslav Generation: The Rethinking of Youth Politics and Cultures in Late Socialism.

Manchester University Press have now published Dr Ljubica Spaskovska‘s new book – The Last Yugoslav Generation: The Rethinking of Youth Politics and Cultures in Late Socialism.

Her monograph examines the development of youth culture and politics in socialist Yugoslavia, focusing specifically on the 1980s. Rather than examining the 1980s as a mere prelude to the violent collapse of the country in the 1990s, the book recovers the multiplicity of political visions and cultural developments that evolved at the time and that have been largely forgotten in subsequent discussion. She argues that the youth of this generation sought to rearticulate the Yugoslav socialist framework in order to reinvigorate it and ‘democratise’ it, rather than destroy it altogether.

Ljubica Spaskovska is an Associate Research Fellow working on our research project 1989 after 1989 at the University of Exeter. Her research maps the history of the end of Yugoslavia’s global engagements not only as a subject/phenomenon associated with political/diplomatic history, but also as a broader societal project.

Ljubica Spaskovska is an Associate Research Fellow working on our research project 1989 after 1989 at the University of Exeter. Her research maps the history of the end of Yugoslavia’s global engagements not only as a subject/phenomenon associated with political/diplomatic history, but also as a broader societal project.

→ Purchase The Last Yugoslav Generation

[Top]

(Re)Thinking Yugoslav Internationalism Conference Programme now available

Posted on 26 September, 2016 in1989 after 1989 Cold War Eastern Europe End of Yugoslavia Globalisation Post Socialism Socialism

(Re)Thinking Yugoslav Internationalism – Cold War Entanglements and their Legacies

29 September – 1 October 2016

VENUE:

University of Graz

Meerscheinschlössl / Festsaal

Mozartgasse 3

8010 Graz

** Please be aware that the conference venue has recently changed and will no longer be at Merangasse 70, Universitatszentrum. **

→ Google Map of Meerscheinschlössl

The conference programme is now available for our collaborative conference taking place this Thursday to Saturday in Graz, Austria.

It will open at 4pm on the 29th September with a welcome address from Professor Florian Bieber, University of Graz, followed by a Keynote speech from Kristen Ghodsee of Bowdoin, USA, entitled Women in Red: East European Mass Women’s Organizations and International Feminism during the Cold War.

Panels on Friday 30th will include papers on the theory and practice of Non-Alignment and Yugoslav foreign policy as well as elite socialisation and Global Actors. The day will conclude with a Keynote speech from 1989 after 1989’s Professor James Mark.

The final day of the conference will feature a witness panel discussion with Budimir Loncar – the last Yugoslav Minister of Foreign Affairs; as well as papers on race, anti-Colonialism and Yugoslavia in post-Colonial Africa; economics, self-management and visions of non-capitalist development; the United Nations, international law, gender and development; and tourism, architecture and cultural diplomacy.

More information on the conference can be found on our conference page and on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/events/1088023487942103/

[Top]Join us for our (Re)Thinking Yugoslav Internationalism Conference in Graz, 29 September – 1 October

Posted on 20 September, 2016 in1989 after 1989 End of Yugoslavia Globalisation Rethinking 1989 Socialism

Coinciding with the 55th anniversary of the Belgrade summit and the foundation of the Non-Aligned Movement, this conference will address a range of questions relating to the wealth of diplomatic, economic, intellectual and cultural encounters and exchange between 1945 – 1990, both within the Non-Aligned Movement, across the socialist world and with the developed countries. It will map the history of Yugoslavia’s global engagements not only as a subject associated with political and diplomatic

history, but also as a broader societal and cultural project.

This is a collaborative conference between ourselves and the Centre of Southeast European Studies at the University of Graz.

WHERE:

University of Graz

Meerscheinschlössl / Festsaal

Mozartgasse 3

8010 Graz

→University of Graz campus map

WHEN:

29 September 16:00 – 19:00 1 October

KEYNOTE SPEAKERS:

Professor Kristen Ghodsee

Professor Kristen Ghodsee

Bowdoin University, USA

Professor James Mark

Professor James Mark

University of Exeter & 1989 after 1989, UK

[Top]

Workshop: Labour Mobility in the Socialist World and its Legacies, Oxford 19-20 May 2016

Posted on 10 May, 2016 inEastern Europe End of Yugoslavia Globalisation Post Socialism Socialism

Interested in hearing Professor James Mark keynote speech on socialist globalization and the research work of Dr Ljubica Spaskovska on Yugoslav investment construction and labour mobility? Then why not come along to a workshop hosted by the University of Oxford on the 19-20 May. Papers given at the workshop will also present research work taking place as part of the Socialism Goes Global project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the University of Exeter.

WORKSHOP: LABOUR MOBILITY IN THE SOCIALIST WORLD AND ITS LEGACIES

19-20 May 2016

European Studies Centre, University of Oxford

Workshop Synopsis

Almost 30 years after the crumbling of the state-socialist regimes in Eastern Europe, the conceptualisation of the state-socialist era as a time of immobility and isolation continues to linger. This portrayal utterly misses the robust flows of people, technology, goods, knowledge and capital that took place between socialist states worldwide. Recently, scholars from a variety of disciplines have begun to map these socialist circulations. The planned workshop will build on these pioneering efforts with the goal of furthering the understanding of these complex flows – particularly those involving workers and technical staff – within the erstwhile socialist world.

Some of the socialist circulations, such as the stays by thousands of university students from Africa, Asia and Latin America in various Eastern European countries, have already received some scholarly attention. However, other forms of mobility, such as state-socialist labour migrations, remain largely unexplored. Yet, examples abound: the Vietnamese government dispatched thousands of its teachers, engineers, agronomists, doctors and planners to Madagascar, Guiney, Algeria, Angola and Mozambique; Cuba sent both its intelligentsia and its blue-collar workers to Europe for training and work and simultaneously provided secondary and university education to 30,000 people from the sub-Saharan Africa; Vietnamese, Cubans and Mozambicans travelled for vocational training or as contract workers to the GDR, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, the Soviet Union, Hungary and Poland; many engineers, doctors, and military officers from eastern Europe travelled in the opposite direction to help build power stations, cement factories or hospitals and to train local personnel for them on site. Labour mobility took place within regions too: Hungarians and Poles, for instance, crossed the border daily or weekly to work in Czechoslovak companies. In short, the world of socialist labour mobility was complex one: It was multidirectional, crossed local borders, spanned world regions, was simultaneously an economic, political and cultural phenomenon.

We also wish to address the contemporary incarnations and the legacy of these past circulations. Business and trade links still follow some of the earlier patterns of socialistera mobility. Some of the experts and students who were trained and socialised in a broader socialist world of the late Cold War continue to hold high positions in many countries and thus shape these countries global engagements today.

PRELIMINARY PROGRAMME

Thursday, 19 May 2016

Arrival, meet & greet, light lunch served at the European Studies Centre from 12:15

13:00–13:15: Opening remarks: Alena Alamgir

Panel 1 – 13:15–15:15 – Labour mobility between the Soviet centre and peripheries (Chair TBA)

- Malika Bahovadinova: “Building the state and the proletariat on a Soviet construction site in Tajikistan.”

2. Kateryna Burkush: “On the forest front: Mechanisms of seasonal labour migration under late socialism (1960s–1980s). The case of Western Ukraine.”

3. Leyla Sayfutdinova: “Mapping the mobility of Azerbaijani Soviet engineers: linking West and East?”

Break 15:15-15:35

Panel 2 – 15:35–16:45 – Technological flows and exchanges (Chair TBA)

- Ljubica Spaskovska: “‘Constructing a better world’ – Yugoslav investment construction and labour mobility in the developing world 1960-1990”

2. Patryk Babiracki: “Labour mobility at the Poznań International Trade Fair, 1940s– 1960s” Break 16:45–17:05 17:05–18:15: “Mini-keynote” on labour migration by Andreas Eckert, roundtable discussion

Friday, May 20th

Panel 3 – 9:00–11:00 – Overseas blue-collar workers in state-socialist Central Europe (Chair TBA)

- Alena Alamgir: “’They knit sweaters and refuse to follow foreman’s orders’: Vietnamese female workers’ labour disputes in 1980s Czechoslovakia”

2. Balint Tolmar: “Socialist assistance under a regime of austerity: The case of Cuban temporary workers in Hungary, 1980–1989”

3. Marcia Schenck: “Legacies of Mozambican and Angolan labour migration to the GDR: ‘East-algia’ and continuing protest“

Break 11:00–11:20

Panel 4 – 11:20–12:30 – Expert migrations (Chair TBA)

- Klejd Këlliçi: “Chinese specialist in Albania 1961-1978: From brothers and heroes to villains”

2. Agnieszka Sadecka: “Polish experts in India as represented in works of nonfiction from 1960s and 1970s”

12:30–13:30: Lunch

13:30–14:40: “Mini-keynote” on socialist globalization by James Mark, roundtable discussion, summary, and conclusion of the workshop

For more information about this event please contact Catherine Devenish: c.devenish@exeter.ac.uk or email european.studies@sant.ox.ac.uk

Socialism Goes Global website: http://socialismgoesglobal.exeter.ac.uk/

[Top]Call for Papers: (Re)Thinking Yugoslav Internationalism – Cold War Global Entanglements and their Legacies

Posted on 14 December, 2015 in1989 after 1989 Cold War End of Yugoslavia Globalisation Rethinking 1989 Socialism

Graz, Austria

Centre for Southeast European Studies, University of Graz and the University of Exeter

30 September – 1 October 2016

Call for Papers Deadline: 28 February 2016

(Re)Thinking Yugoslav Internationalism – Cold War Global Entanglements and their Legacies

For more than forty years, Yugoslavia was one of the most internationalist and outward looking of all socialist countries in Europe, playing leading roles in various trans-national initiatives – principally as central participant within the Non-Aligned Movement – that sought to remake existing geopolitical hierarchies and rethink international relations. Both moral and pragmatic motives often overlapped in its efforts to enhance cooperation between developing nations, propagate peaceful coexistence in a divided world and pioneer a specific non-orthodox form of socialism.

Although the disintegration of socialist Yugoslavia has received extensive treatment across a range of disciplines, the end of Yugoslavia’s global role and the impacts this had both at home and abroad, have received little attention. Coinciding with the 55th anniversary of the Belgrade summit and the foundation of the Non-Aligned Movement, this conference seeks to open up a range of questions relating to the wealth of diplomatic, economic, intellectual and cultural encounters and exchange between 1945 – 1990, both within the Non-Aligned Movement, across the socialist world and with the developed countries. It would map the history of Yugoslavia’s global engagements not only as a subject associated with political/diplomatic history, but also as a broader societal and cultural project. Important witnesses involved in those exchanges and alliances will also be invited to share their experiences.

We welcome papers from different disciplines and from diverse perspectives, whether dealing with aspects of Cold War international cooperation, development, Yugoslavia’s global role, or the ‘global’ Cold War from the perspective of the developing world and the ‘global South’. We particularly encourage proposals which would reflect on:

- the roots of Yugoslav internationalism and how it was understood in cultural/economic/social as well as political/diplomatic terms;

- the contours of Yugoslav diplomacy and the ways Yugoslav elites conceptualised their global role;

- the role of Yugoslavia in the United Nations, its agencies and other international organisations as the fora for global encounters and in particular the attempts at tackling global inequality and alternative development;

- the relationship between Yugoslavia, the different liberation movements and the newly emerging independent nations in the ‘global South’ (including cultural diplomacy, labour migration, individual travel);

- the realities and challenges of foreign trade, investment construction and economic cooperation;

- the ways international engagements reshaped aspects of political, economic or cultural life back in Yugoslavia;

- the role and significance of the Non-Aligned Movement during the Cold War and today;

- the international impact of the end of Yugoslavia and the collapse of her global role;

- the legacies and new understandings of Yugoslavia’s global role.

Abstracts of 300-500 words, together with an accompanying short biographical note should be submitted to Natalie Taylor (N.H.Taylor@exeter.ac.uk) by 28 February 2016.

Funding opportunities for travel and accommodation are available, but we ask that potential contributors also explore funding opportunities at their home institutions.

This event is kindly supported by the Centre for Southeast European Studies and the Leverhulme Trust-funded project 1989 after 1989: Rethinking the Fall of State Socialism in Global Perspective at the University of Exeter.

[Top]‘Death to fascism, freedom to expression!’ – The Post-Yugoslav Media and Freedom of Speech

Posted on 3 November, 2014 in1989 after 1989 End of Yugoslavia Human Rights

By Ljubica Spaskovska

The transition to democracy should have liberated the media in the former Yugoslav states, but in many ways the situation has actually gotten worse.

‘In these times/when everything is silent/In these times/I say – freedom/ And I see fear…’

This verse from the song entitled ‘Freedom’ is one of the tracks from an album by the Macedonian band ‘Reporters’ made up exclusively of journalists of different ethnic backgrounds. Under the slogan ‘Solidarity for freedom’, the Independent trade union of journalists and media workers, with the support of the US Embassy launched a campaign meant to incite a debate on freedom of speech, on the state of the media in Macedonia and solidarity among journalists. Over the past few weeks, both Macedonia’s and Serbia’s Independent Journalists’ Associations (members of the International Federation of Journalists) have raised concerns about similar phenomena through calls for a public hearing on media freedom or through the organisation of debates, conferences and concerts.

Indeed, the 2014 EU progress reports for all of the post-Yugoslav states aspiring to EU accession (Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, Kosovo, Macedonia) underline a trend of serious deterioration of media freedom. Almost quarter of a century after the disintegration of Yugoslavia and the introduction of electoral, multi-party democracy, these societies have been witnessing a progressive narrowing down of public, intellectual and media spaces for free debate and reporting. Political and financial pressures, intimidation and threats against journalists and editors in Bosnia, self-censorship, threats and violence against journalists in Serbia, Montenegro and Kosovo, and government influence on media exercised through state-financed advertising in Macedonia have been observed in a context of a scarcity of real commitment on the part of political elites to tackle this problem and take the recommendations from the progress reports seriously.

Over the years, different governments have managed to blur the line between the ruling party/coalition and the state and to deprive state institutions of their independence. Moreover, they have turned an increasing number of media outlets into channels for dissemination of their political ideology or attacks on political opponents. For instance, the State Department Macedonia Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 2013 noted that members of the Association of Journalists of Macedonia reported pressures ‘to adopt a pro-government viewpoint in their reporting or lose their jobs.’

In Macedonia, further grievances were aroused by the detention and conviction of journalist Tomislav Kežarovski for revealing the identity of a protected witness in a story written in 2008. Civil society activists, local journalist associations and opposition leaders have constantly referred to reports by international bodies and governments that had condemned the trial and Kežarovski’s imprisonment in order to give legitimacy to their protest, albeit to little avail.

Moreover, the State Department Country Report lists Kežarovski’s case in the section entitled ‘Political Prisoners and Detainees’. The OSCE Representative for the Freedom of the Media, as well as the European Federation of Journalists similarly condemned the long sentence. Hence, it comes as no surprise that in the 2014 World Press Freedom Index Macedonia sits in 123rd place and has never been so low in the Index (the lowest in comparison to the other former Yugoslav states).

However, the state of the media is only a symptom of wider societal phenomena such as growing intolerance toward ‘oppositional’ voices and certain frozen narratives which seek to uncritically glorify the nation, the state, the ruling ideology and demonize the socialist/Yugoslav past. Croatia and Slovenia are the only two former Yugoslav republics which are members of the European Union. Although considerably higher on the World Press Freedom Index, neither Slovenia nor Croatia have been immune to the (re)establishment of a certain dogmatism in interpreting or discussing about the past.

A case in point is the recent decision of Croatian President Ivo Josipović to fire his main analyst professor Dejan Jović for an article in the academic journal Political Thought. Entitled ‘Only in myths every nation desires its own state’ and comparing the Scottish independence referendum and the Yugoslav referenda of the early 1990s, Jović argued that the latter were illiberal and did not allow for a genuine debate and consideration of all political opinions and visions for Yugoslavia’s future.

Similarly, the MPs of the conservative Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) proposed a dismissal of the president of the Slovenian national assembly Dr. Milan Brglez for qualifying Yugoslavia in an interview as a state that had credibility and prestige in the international community and that the Slovenian independence in that sense was a step backwards.

Why, a quarter of a century after the first multi-party elections in the former Yugoslavia, are there still certain dogmatic ‘truths’ in most of the successor states, where freedom of expression is not an accomplishment, but, rather, something yet to be realised?

An obvious reason which is often evoked as the main factor is the socialist past itself. However, this can only offer a partial explanation and it could be counter-productive, as it fails to put the burden of responsibility on contemporary policy-makers and elites. Moreover, from 1950 practices of pre-censorship had been abolished in socialist Yugoslavia. It was the public prosecutor who could act only ex-post facto, after a broadcast, publication or film presentation. By the mid-1980s, the Yugoslav media network was significantly fragmented, decentralised, yet numerically impressive.

In 1987, Yugoslavia had 2,825 newspapers and 202 radio and TV stations. Hence, it was virtually impossible to sanction all acts which were classified as ‘verbal crime’ under the notorious ‘Article 133’ which criminalised acts of ‘hostile propaganda’, but was also meant to curb nationalist discourse, channelling what Lenard Cohen identified as ‘Yugoslav communism’s strong antipathy to overt nationalist tactics’.[1] Moreover, the 1980s saw the reinvigoration of the debate on freedom of speech and on the abolishment of the verbal crime. Although restrained, debate did occur in different fora.

For instance, in 1981 the president of the Federal Court in an article in a law journal acknowledged that the formulation of ‘Article 133’ was not precise, while at the 1983 conference of Yugoslav criminologists several professors of law called for the repeal of the article.[2] Several years later, as a young journalist in one of the principal magazines of the League of Socialist Youth, Dejan Jovic argued that the organisation (which in fact financed the magazine) should be abolished [3]. Back then, he was not sacked for his opinion.

Twenty-five years later, both old and new generations of journalists, intellectuals, students and activists are fighting battles which would have normally belonged to a distant past. When on 9 May last year, on the occasion of Europe Day, representatives of the ‘Front for Freedom of Expression’ gathering a number of civil society organizations and initiatives staged a protest in front of the seat of the delegation of the European Union to Macedonia, they chose as their slogan a creative remake of an old motto of the partisan resistance movement: ‘Death to fascism, freedom to expression!’.

References:

[1] Lenard Cohen, The Socialist Pyramid Elites and Power in Yugoslavia(Oakville/New York/London: Mosaic Press, 1989), p.445.

[2] Yugoslavia: Prisoners of Conscience (London: Amnesty International Publications, 1985), p.29.

[3] Dejan Jović, ‘Kad bi SSOJ postojao, trebalo bi ga ukinuti (1)’ Polet 402, 10.2.1989.

[Top]The Future of the Past: Why the End of Yugoslavia is Still Important

Posted on 31 March, 2014 in1989 after 1989 End of Yugoslavia

By Ljubica Spaskovska

A new socialist model is emerging in the western Balkans. Can its political vocabulary transcend the ethno-national dividing lines in the region?

‘New project for democratic socialism in Yugoslavia’ read the title of the resolution for the last congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. It was January 1990.

As the Yugoslav Party was writing the last pages of its seventy-year old existence, few were left who believed in the viability of the project of democratic socialism. ‘The liberal utopia which underpinned 1989’ was the idealized way the socialist East and South imagined ‘the West’ and liberal democracy. In the aftermath of the last Yugoslav party congress, even fewer could imagine that ‘democratic socialism’ could ever be resurrected as a viable political project.

Almost a quarter of a century later, however, the Slovenian ‘Initiative for democratic socialism’, the Democratic Labour Party and the Sustainable Development Party have announced the establishment of a ‘United Left’ coalition. These non-parliamentary leftist groups will present their bid for a new socialist model in Europe at the upcoming EU elections in May. While the recent wave of protests in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and on a smaller scale in Macedonia, have raised social concerns and acted as a vent for rebellion against the political and economic mismanagement by elites, Kosovan students at the University of Prishtina made a strong case against structural corruption and fraud, eventually succeeding in deposing the Rector.

Many of those who found themselves at the forefront of these ‘acts of citizenship’ have been young people who came of age in the post-socialist period. The Kosovan student protesters, the Macedonian activists for social justice in the leftist groups ‘Solidarity’ and ‘Lenka’, the organizers of the Zagreb Subversive Forum, and the activists in the Slovenian Initiative for democratic socialism, belong in a pool of activists groups, initiatives or centres for research that espouse progressive politics while they have sought to deconstruct the ‘liberal utopia’ of the post-socialist period. They are unquestionably part of a new political generation (or, a ‘generation unit’, to use Mannheim’s terminology) whose political subjectivities, demands and visions represent a departure from those that twenty-five years ago ushered in the post-Yugoslav era.

How to account for this sudden post-Yugoslav outburst of social discontent and the resurrection of a long-forgotten vocabulary, where social rights, democratic socialism, the working class and the dispossessed feature rather prominently? Beside the generational factor, one possible answers lies in the concluding paragraph of last month’s open letter to the international community signed by 130 scholars and academics from around the world:

“In [the] spring of 1992, Bosnian citizens staged in Sarajevo the largest demonstrations ever against all nationalist parties. They were silenced by snipers, and their voices, from that point on, ignored by the international community. This time, the world should listen.”

Indeed, the conventional narrative of the 1980s, as the climax of political skirmishing and ethnic hostility, has so far managed to conceal a major stream of critique that was silenced by the subsequent armed conflicts and progressively erased in the new nation-states. The last Yugoslav public opinion survey conducted in 1990, from a sample of 4,230 adults, revealed clear divisions along lines of ethno-national belonging.

However, there was one part of the survey where Yugoslav citizens appeared strikingly unanimous. Namely, respondents were asked if expenditures on education, culture, healthcare and social security should be reduced. 74% of Bosnians, 66% of Montenegrins, 81% of Croatians, 71% of Macedonians, 72% of Slovenes, 79% of Serbs, 80% of Kosovans and 84% of Vojvodinians said this budget should be either increased or the present level of spending should be maintained. Moreover, the survey found that the ‘democratic optimism’, i.e. a support for a multi-party system was highest among Kosovans and Slovenes (19%) and lowest in Bosnia-Herzegovina (4%). Indeed, respondents from ethnically-mixed regions expressed fears that a multi-party system would exacerbate inter-ethnic divisions.

One of the spheres where many of these debates took place during the 1980s was the Yugoslav press and, in particular, the so far scarcely researched youth press. A commitment to exposing socio-economic structural inequalities and forms of corruption, especially among top Party officials, came to define the increasingly vocal youth press that was subject as a result to ongoing bans, trials and public discrediting throughout the 1980s. This led foreign scholars to observe that:

“Of all the periodical publications appearing in Yugoslavia, it is the youth press which has proven the most consistently nettling to the authorities. Outspoken to the point of rebelliousness, the young editors […] have repeatedly ignored even the most fundamental taboos”.

Pedro Ramet, ‘The Yugoslav Press in Flux’, in Pedro Ramet (ed.) (1985), Yugoslavia in the 1980s, p.111

Young journalists tended to link these phenomena to the authoritarian traits of Yugoslav socialism, in particular the Party’s elites and their monopoly on power. In December 1984, for instance, the Croatian youth magazine Polet published an ironic call for the ‘Big, bigger, the biggest Yugoslav competition for the photograph of the most beautiful, richest, most luxurious and most unavailable house for the working class on the territory of the former Yugoslavia’, printed over a black and white photo of a big mansion. It also noted that ‘precedence will be given to the photographs which will also supply information about the location, the size, the owners and their occupation’. Four years later, the main Bosnian youth magazine Naši dani was at the helm of a big public debate which exposed the practice of building summer villas by high Bosnian political officials at the sea-side resort of Neum. One article unreservedly attacking high-ranking politicians put forward demands which could be heard in a modified form at recent protests: ‘To nationalise what had been robbed. To take away once and for all from the red bourgeoisie and give to the working class’. Finally, a similar affair burst into the open when Slovenian youth magazine Mladina accused the federal Minister of Defense of having a summer villa constructed for himself by army recruits in the sea resort of Opatija.

As the decade drew to a close and the Yugoslav sonderweg led many to believe that the multi-level crisis was a dead-end street and that violence was looming, many voices warned at the prospect of elites capitalizing on social discontent and posing as national saviours. Even regions like Macedonia, which were later spared from the violence of the dissolution conflicts, were mired in a new nationalist rhetoric and calls for prohibition of ethnic minorities’ political parties. The way the editor-in-chief of the youth magazine Mlad borec, Nikola Mladenov targeted the rise of nationalism in his editorials, both at Yugoslav and local level, captures this:

“As if it became a civic duty to propagate national tragedy and vulnerability. In place of one collectivity – the class, we are being offered another one – the nation, the easiest way of manipulating the emotions of tomorrow’s voters. The propagating of one’s one history – always the most bloody and most difficult – hasn’t bypassed us either […]”

For two and a half decades former Yugoslavs were repeatedly reminded of their national tragedies, bloody histories, or their victimhood at the hands of neighbours. They were encouraged, if not forced, to erase out of their memories and identities that other collectivity – the class. What the Bosnian student magazine Valter wrote in 1990 indeed reads like a prophecy:

“We should not have any doubts that this is a period where we’ll see a formal change of government, accompanied by strong disillusionment of manipulated voters. Because exclusive anti-communism does not imply automatic creativity; on the contrary, the motives are quite banal and easily recognisable – taking power.”

A generational shift, growing inequality, deterioration in living standards and the withering away of social rights have undoubtedly proved crucial for the emergence of a new political vocabulary and a range of demands which appear to neglect, if not transcend, the ethno-national frame. However, it remains to be seen whether the social(ist) utopia that underpins this shift is going to successfully restore some of the betrayed hopes of the late 1980s.

Bibliography:

George Lawson, Chris Armbruster and Michael Cox (eds.), The Global 1989: Continuity and Change in World Politics (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Ljuljana Baćević, et al. Jugoslavija na kriznoj prekretnici (Beograd: Institut društvenih nauka/Centar za politikološka iztraživanja i javno mnenje, 1991).

Pedro Ramet, ‘The Yugoslav Press in Flux’, in Pedro Ramet (ed.), Yugoslavia in the 1980s (Westview Press, 1985), p.111.

‘Veliki, veći, najveći’, Polet 292, 21.12.1984, p.10.

Radmilo Milovanović, ‘Neum ili dolje crvena buržoazija’, Naši dani 949, 2.9.1988, p.7.

Nikola Mladenov, ‘Народе македонски’, Mlad borec 1971, 07.03.1990.

Goran Todorović, ‘Sveti Ante’, Valter 28, 17.4.1990, p.2.