1989 after 1989 Research Fellow Awarded Fritz Stern Dissertation Prize

Posted on 9 December, 2014 in1989 after 1989 Human Rights

Many congratulations to our Research Fellow, Dr Ned Richardson-Little, on being awarded the prestigious 2014 Fritz Stern Dissertation Prize.

He received the award at the 23rd Annual Symposium of the Friends of the German Historical Institute in Washington DC last month, where Richardson-Little also spoke about his dissertation and his research.

His PhD dissertation: Between Dictatorship and Dissent: Ideology, Legitimacy and Human Rights in East Germany, 1945-1990 (Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2013) was praised by the German Historical Institute (GHI) for being an “intellectually challenging and beautifully written study of human rights politics in the German Democratic Republic”. The GHI also commended his work for it’s significant and timely contribution to both historiography on modern Germany and the emerging scholarship on human rights.

His PhD dissertation: Between Dictatorship and Dissent: Ideology, Legitimacy and Human Rights in East Germany, 1945-1990 (Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2013) was praised by the German Historical Institute (GHI) for being an “intellectually challenging and beautifully written study of human rights politics in the German Democratic Republic”. The GHI also commended his work for it’s significant and timely contribution to both historiography on modern Germany and the emerging scholarship on human rights.

The GHI’s prize citation reads:

Edward Richardson-Little’s dissertation, “Between Dictatorship and Dissent: Ideology, Legitimacy, and Human Rights in East Germany, 1945-1990,” is an intellectually challenging and beautifully written study of human rights politics in the German Democratic Republic. Upon learning that leaders and supporters of the ruling Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (SED) often invoked human rights, one might be tempted to imagine this practice as a cynical use of rhetoric by a dictatorial government to combat a rival Western vision of democracy and capitalism. However, Richardson-Little persuasively demonstrates that the SED and its supporters convinced many religious leaders, intellectuals, and working class supporters that socialism supported an indigenous brand of human rights superior to the individualistic, liberal version offered by the West. Richardson-Little makes excellent use of a wide range of sources from fourteen German archives to argue that, not only was there a thriving debate about human rights in East Germany, but also that citizens used that discourse to express dissent. Quite early, the SED developed its own Marxist conception of human rights to criticize the West, including the dangers of Western imperialism. The East German regime encouraged its citizens to believe that there could be “no human rights without Socialism.” The SED established a Committee for Human Rights, argued for human rights solidarity in the Third World, and used human rights as a basis for international agreements with the West. By the mid-1980s the discourse of human rights fostered by the SED provided peace activists, environmentalists, and advocates of democracy a powerful tool to oppose East German policies as well. The strength of their arguments helps explain the speed of revolutionary impulses by 1989. The SED’s use of human rights discourse, Richardson-Little demonstrates, played a critical role in legitimizing its own downfall. The topic of human rights has received a great deal of scholarly attention from recent historians, largely as part of narratives of the spread of Western values. However, as Richardson-Little points out, contradictions between a rhetoric of human rights and political policies that violate those rights characterized Western powers as well. Historians should be no less willing to accept that contemporaries in East Germany could value human rights, even if their envisioned path to achieving those rights varied significantly from their Western counterparts. In the face of continued debates about the limits of the West’s commitment to human rights, Richardson-Little’s Between Dictatorship and Dissent thus makes a significant and timely contribution, both to the historiography on modern Germany and to the emerging scholarship on human rights.

Richardson-Little will now continues his research with the 1989 after 1989 project at the University of Exeter, where he seeks to complicate the triumphalist narratives of good inevitably overcoming evil, ushering in a unified global human rights culture, by examining the complexity and plurality of human rights in late socialism and the post-socialist world. More information on Dr Richardson-Little research can be found here.

Writing Human Rights into the History of State Socialism

Posted on 24 March, 2014 in1989 after 1989 Human Rights

By Ned Richardson-Little

One of a number of East German postage stamps commemorating International Human Rights Year 1968. The hammer and anvil represent the right to work

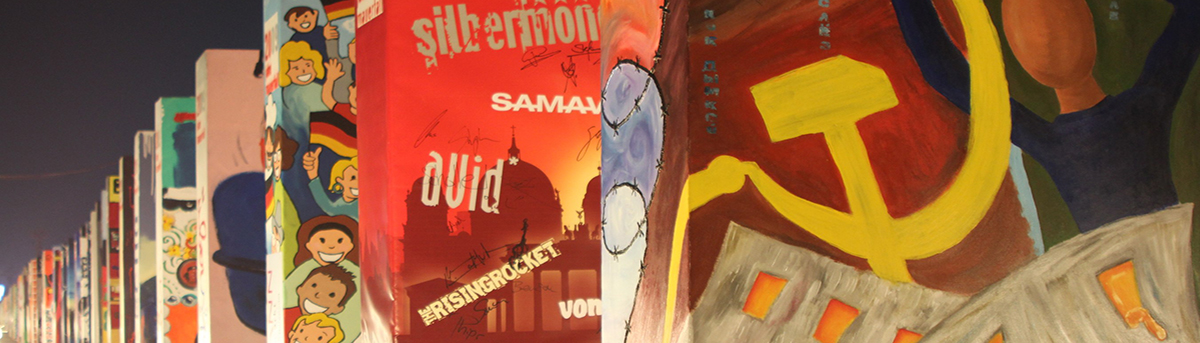

The collapse of the Communist Bloc in 1989-1991 is viewed as one of the great triumphs of the human rights movement. But this ignores how socialist elites of the Eastern Bloc viewed themselves: not as the villains in the story of human rights, but as the champions.

In recent years, the rapidly expanding field of human rights history has done much to complicate triumphalist narratives of inevitable victory for Western liberal democracy over the forces of tyranny. Recent collections including those edited by Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann, Jan Eckel and Samuel Moyn, have opened up new lines of inquiry exposing not only the contingency of these ideas, but also the conflicts amongst those claiming the mantle of universal human rights. On the Exeter University Imperial and Global History Centre blog in recent weeks, Fabian Klose has examined the important role of decolonization and post-colonial states in shaping the development of human rights politics, and Robert Brier has interrogated the idea of human rights as a product of neo-liberalism in the context of the Polish opposition. Here, I want to look beyond the human rights campaigns of dissident Eastern Europeans to that of the states they fought against.

While state socialism is normally seen as the definitional opponent of human rights – rejecting individual autonomy, independent justice, free elections, free speech and free practice of religion – the elites of the Eastern Bloc claimed that they were actually the true representatives of human rights. For them, the revolutionary victory over capitalism meant the end of class conflict and the abolition of the “exploitation of man by man.” The creation of a socialist society overcame the horrific abuses of the capitalist system, including war, imperialism and racism.

Another stamp commemorating International Human Rights Year 1968. The tree and globe represent the right to life

Eastern Bloc elites built upon Karl Marx’s denunciation of human rights rhetoric as a tool of the bourgeoisie to disguise their own class interests in the cloak of universal justice. They argued that while human rights were indeed a sham under capitalism, the socialist revolution had created a higher kind of human rights that allowed for real participation in all forms of political and economic life and achieved true equality across the class, race and gender lines. As the East German legal philosopher Karl Polak declared, “There can be no human rights without socialism!”[1]

When such rhetoric from the Eastern Bloc has been noted in histories of the Cold War, it is usually dismissed as a crude and cynical attempt to deflect Western criticism, particularly after the signing of the Helsinki Accords in 1975. That is, once the communist states were compelled to affirm the idea of human rights, they simply had to adjust their rhetoric in a desperate attempt to fend off protest from within and without.[2] These narratives are undermined, however, by the fact that state socialist elites were using the language of human rights well before Helsinki – the quote above from Karl Polak dates to 1946. In Hungary, the first scholarly work on human rights and socialism was written by legal scholar Imre Szabo in 1948.[3] As Jennifer Amos and Daniel Whelan have demonstrated, the Soviet Union was an active player in the human rights diplomacy of the 1950s. Such early efforts weren’t just rhetorical or academic: the German Democratic Republic formed the Committee for the Protection of Human Rights to campaign against abuses by the West and to mobilize citizens to campaign against the imprisonment of communists and peace activists in West Germany. Founded in 1959, this group predates the creation of Amnesty International by two years.

The 1970s are today seen as the turning point when international human rights exploded as a global movement, but at the beginning of the decade, it appeared to some observers that the West was simply outmatched by the Socialist Bloc. By 1968, the entirety of the Eastern Bloc had either signed or publically affirmed the UN’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. While the United Kingdom, Italy, and West Germany did so early on, other Western countries lagged well behind with Canada signing in 1976, the USA in 1977 and France in 1980. In 1973, one observer from West Germany concluded,

With the change in majorities in the bodies of world organizations – particularly in the [UN] General Assembly – the socialist states have recognized the possibility of the politicization of human rights, and the free world has almost cleared off the field without a fight: the US by its human rights abstinence, the Western European countries by their regionalism.[4]

While the Helsinki Accords are now often portrayed as a coup for the West in “forcing” the East to accept terms that would eventually lead to its downfall, at the time, the idea of human rights was hardly seen as a devastating ideological weapon.

Including the perspective of state socialist leaders and elites is crucial to understanding human rights diplomacy in the post-war era. Such ideas and politics also were crucial to state socialist rule and influenced the development of dissident and opposition movements, as I have recently argued, along with Benjamin Nathans, Paul Betts, and Mark Smith and others. Celia Donert’s recent work similarly demonstrates how the explosion of women’s rights as human rights in 1990s can be in part traced back to the transnational feminism organized through Eastern Bloc organizations and events that have been dismissed as mere propaganda for communism. Rather than simply seeing the rise of human rights movements in the East as a direct importation from the West, this new scholarship shows how 1989 was also connected to the evolution of indigenous right cultures that were initially fostered by the state. This line of inquiry is not only valuable to the study of the Cold War and its end, but also to explaining the development of human rights politics in the post-socialist period.

In challenging liberal Western triumphalism, it is also vital to consider the perspectives of the socialist East. The appropriation of the idea of human rights by non-liberal and even dictatorial states is no relic of Cold War dynamics long since departed, but is continuing to this day in Iran and North Korea. In grappling with the developments of 1989, political scientist Peter Juliver argued that one had to begin a process of “rethinking rights without the enemy.” I would argue that in order to do so, we first must rethink the history of human rights including the “enemies,” and not just the victors.

[1] Karl Polak, “Gewaltteilung, Menschenrechte, Rechtsstaat: Begriffsformalismus und Demokratie,” Einheit 7 (December 1946): 138.

[2] For the main work asserting the discontinuous effect of Helsinki Accords for the Eastern Bloc, see Daniel Thomas, The Helsinki Effect: International Norms, Human Rights, and the Demise of Communism(Princeton UP, 2001) as well as Michael Ignatieff, Human Rights as Politics and Idolatry, University Center for Human Values series (Princeton UP, 2001), 19, which argues that the Eastern Bloc denied the validity of political and civil human rights prior to Helsinki.